After battling on the lacrosse field as a young man, Neil Powless now fights a different battle: disinformation about the history of his people.

Powless, son of Onondaga Eel Clan Chief Irving Powless Jr., serves as Syracuse University’s ombuds in a small office just off Waverly Avenue. He also responds to educational requests from student reporters and community leaders. Education remains a constant challenge for him and his community — especially under new administrations.

“Every single election cycle, our chiefs, our clan mothers and our community leaders are always re-educating new leaders — re-educating about those relationships, re-educating about our stance on the environment,” Powless said.

As New York state begins its celebration of the Erie Canal bicentennial, the Indigenous communities in upstate New York are disheartened by what they see as a lack of acknowledgement of the trauma the Canal caused their nations. For many members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, Tuscarora and Onondaga nations), the 200th anniversary serves as a painful reminder of encroachment on their territory and a string of broken promises.

The Oneida Nation, for instance, cites 27 illegal treaties used to take their land for the Canal’s construction. Even before its completion, New York Gov. DeWitt Clinton declared that he would help ensure that “before the passing away of the present generation, not a single Iroquois will be seen in this state.”

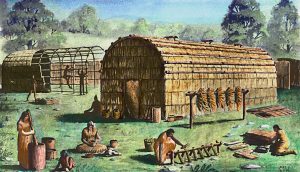

Much of the damage, though, had already been done. In 1779, George Washington ordered the obliteration of Haudenosaunee villages throughout upstate New York. Local historian Steph Adams called the resulting Sullivan-Clinton military expedition a “scorched earth campaign” aimed at destroying the very people who first brought democracy to the Americas and inspiring founders like Benjamin Franklin and Washington himself.

The Sullivan-Clinton campaign ended with the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua with the Haudenosaunee, which established much of upstate New York as Indigenous territory and promised that the United States would never claim the land or disturb its inhabitants. Adams notes that it didn’t take long for the leaders of the new United States to break their word.

“Despite the Treaty of Canandaigua, over time both the federal and state governments would facilitate further dispossession Native lands often through fraud, coercion,” said Adams, who serves as director of interpretation at the Erie Canal Museum. “Many of these treaties revolved around securing land along New York’s natural waterways that would later also hold the Canal.”

Powless said the administration was actively planning on creating the Canal, which would go straight through the land of the Haudenosaunee, disrupting everyday life.

“Construction of the Erie Canal was already planned before the treaty was signed,” Powless said. “So when it was signed, it was immediately broken.”

The Canal’s route through these communities was based on geographic considerations by the government, looking to push European settlers westward without considering the displacement of Indigenous people from their ancestral homeland. Scott Manning Stevens (Akwesasne Mohawk), a history professor at Syracuse University, said white leaders focused on the value of the land and not on what they were taking from the land’s Indigenous occupants.

“Our dispossession becomes part of what it means to build a canal because it’s going to go right through the heartland of our country,” Stevens said. “And it will ratchet up the priority of dispossessing us of our land because it’s too valuable to leave us there.”

The Mohawk River Valley provided a convenient transportation corridor, as it was the only break in the Appalachian Mountain range that allowed for a westward push.

“There was no other place like it; there was a lot of attention placed on this break,” said Philip Arnold, president of the Indigenous Values Institute. “It really was to move white people into the interior of the American continent and to move goods outside of New York City.”

G. Peter Jemison, a renowned Seneca Heron clan artist, said the broken treaties made it apparent that the government was not to be trusted.

“They were not about our rights, they were not about protecting us, they’re always about getting our land,” Jemison said. “All of these treaties, it was just about getting the land from us.”

The construction of the Canal commenced in 1817, and the effects became apparent immediately to the Onondaga Eel clan. Ancient fishing ceremonies and their way of life were disrupted, as the eel itself disappeared.

Powless said part of the reason for the once-abundant eel’s disappearance came from salt mining. As white settlers mined salt from Onondaga Lake and Onondaga Creek, it polluted the traditional fishing grounds. The Canal would also serve as a route for transporting salt from Syracuse to other parts of the state.

“It’s this desecration of Onondaga Lake because the salt mines turned into mudboils, polluting Onondaga Lake and Onondaga Creek,” Powless said. “Those are two major waterways where eel doesn’t exist anymore.”

According to Stevens, Onondaga Lake has become one of the most polluted lakes in the world as a result of the mass industrialization that followed the Canal’s creation. It was at this lake where the Haudenosaunee Confederacy was founded. In the past 100 years, Stevens says, the lake became used as a “garbage dump for chemical slop.”

“They’re not thinking like, ‘Oh, this is not going to be bad for the people that live near it in the future,’” Stevens said. “They’re thinking, ‘How do we make more money?’”

Jemison says the Canal celebration’s exclusion of Indigenous narratives should be scrutinized on a wider scale.

“We’re coming up on this anniversary of the Erie Canal, something that the United States and New York state want to celebrate,” Jemison said. “Yet we, the Indigenous people, are completely excluded.”

Powless is ready to look forward, saying that Indigenous people are ready to walk together with the American government.

“Whatever the path forward is, it’s contributing voices together as equals, as brothers and sisters, not as owner and occupant,” Powless said. “And our people are ready for that, waiting for that.”

“Whenever the American government’s ready for it,” he added, “we’ll be there.”