Buffalo has long been a city caught between preservation and progress.

That tension came to a head in early 2022 when a court ruling sealed the fate of the Great Northern Elevator, a towering relic of Buffalo’s grain industry. As preservationists rallied to save it, the fight over its demolition became about more than just one building — it became a battle over how the city remembers its past.

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Great Northern’s destruction echoed a familiar pattern in a city often at odds with its own architectural heritage.

The Great Northern Elevator was not the first landmark loss for Buffalo’s preservationists. The city has previously seen the demolition of the Larkin Administration Building and the Erie County Savings Bank — structures designed by some of the most influential figures in architecture and engineering, such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Thomas Edison.

Buffalo’s grain elevators tell a story of a city that once reigned as a national shipping and manufacturing stronghold, towering over the city’s harbor from an industrial age long gone.

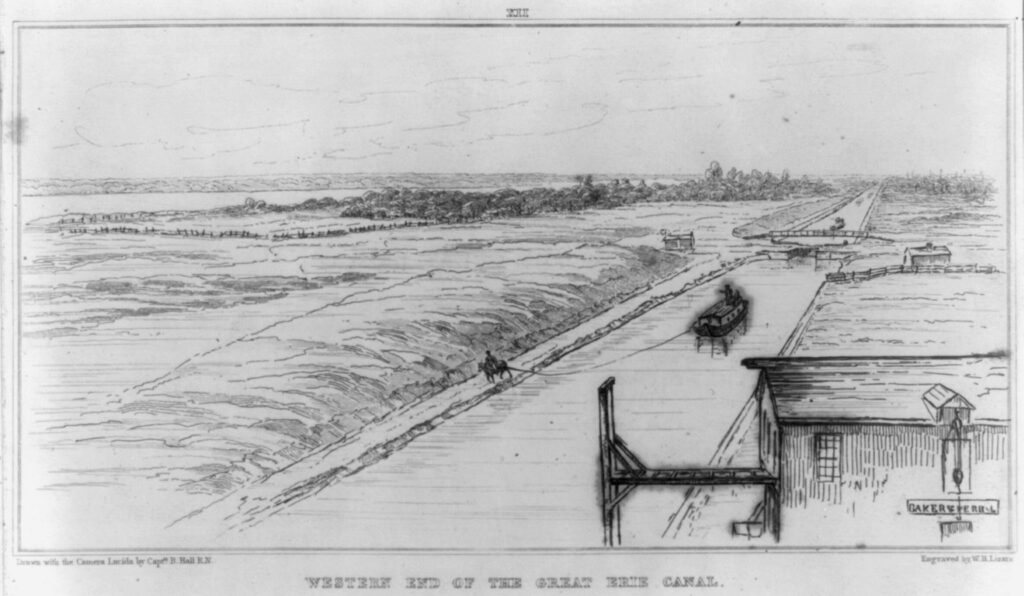

Their existence — and the industrial dominance they resemble — was made possible by the Erie Canal, the engineering marvel that transformed Buffalo from a small frontier town into one of America’s most important cities for a period of time.

Completed in 1825, the Canal connected Lake Erie to the Hudson River, paving the way for commerce to pass through the Appalachians. Buffalo emerged as a key gateway to the Midwest, fueling economic expansion and population growth.

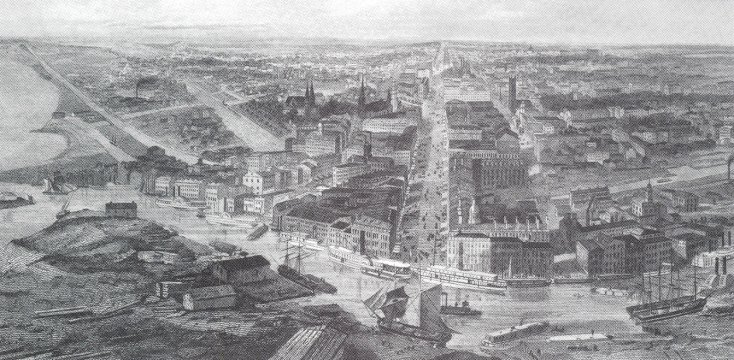

Within a decade, Buffalo’s population surged, growing from just more than 2,000 in 1820 to almost 9,000 in 1830. By the early 20th century, the city was ranked as the eighth most populous city in America, and the grain industry was at the heart of Buffalo’s transformation.

After the construction of the Canal was completed, Buffalo’s grain industry, like its population, grew rapidly. In 1829, four years after the Canal’s opening, the city handled 7,975 bushels of flour and wheat.

A typical bushel weighed around 60 pounds, and by 1830, Buffalo grain saw over 180,000 bushels, about 10 million pounds of grain.

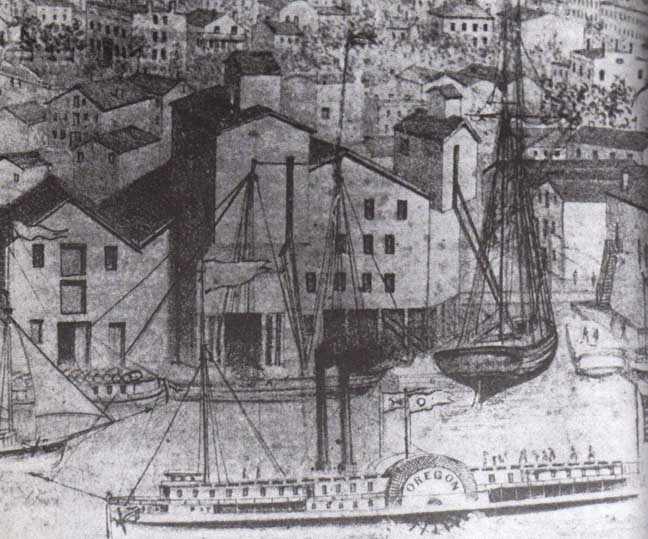

The original process for moving and storing grain was mainly handled by Irish dockworkers, who would cup the grain into buckets and carry it on their backs into warehouses, where the buckets would eventually be weighed and recorded. Compounding the inefficiency, this could not take place during rainy weather, since work was done in the open and moisture damaged the grain. As a result, no more than 2,000 bushels could be moved per day, which resulted in a typically crowded Buffalo harbor.

This bottleneck ended in 1842, when entrepreneur Joseph Dart and mechanical engineer Robert Dunbar introduced the steam-powered grain elevator, an invention that allowed Buffalo to handle massive quantities of grain at a time. A bucket would raise grain from boats along the Buffalo River and move the product to wooden storage bins, transforming the process that took weeks to unload ships into an hourslong operation.

Within 15 years of Dart’s and Dunbar’s invention, Buffalo had become the largest inland port in the United States, shipping millions of bushels annually.

In 1861, the city had 27 grain elevators, and by the end of the Civil War in 1865, it was the world’s leading grain port, surpassing global economic powerhouses like the ports of London, Odessa and Rotterdam.

Most of Buffalo’s elevators were wooden, and the shift to the now-monumental concrete and steel structures was driven by fire risk. In 1900, the total burning of the Eastern Elevator caused over $750,000 in damages, about $29 million in today’s money.

The city’s grain industry peaked between 1925 and the years following World War II, as wartime and postwar Western Europe relied on its grain, with annual receipts reaching up to 300 million bushels, or 18 billion pounds.

But as the city’s fortunes declined in the mid-20th century, driven by the deepening of the Welland Canal and the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway, Buffalo’s time as an industrial powerhouse withered, along with the use of its grain elevators.

As the industry left, so did some of the people. By 1960, Buffalo’s population declined for the first time in its history, and it declined fast. Within 50 years, the city lost half its population, and it didn’t rise again until the 2020 census