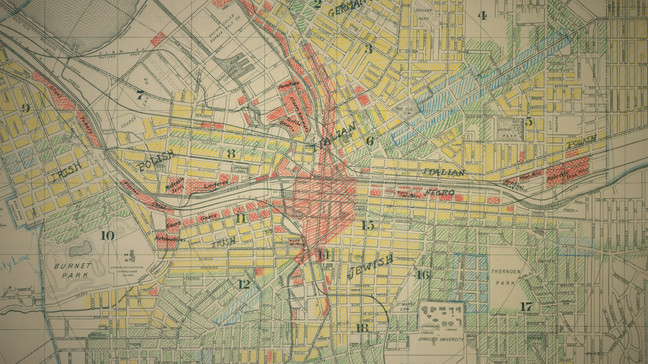

“Restrictive racial covenants barred properties from being sold or rented to people that were not Caucasian,” said Searing on the segregation shown in the Map of 1919. “The Italian people lived with other Italian people, they had a choice, they wanted to. The Irish people and the Polish people, all that is true (too). African Americans did not have a choice of where they wanted to live.”

The practice of forcing Black Americans into certain areas wouldn’t stop even after some of the infrastructure separating races was removed.

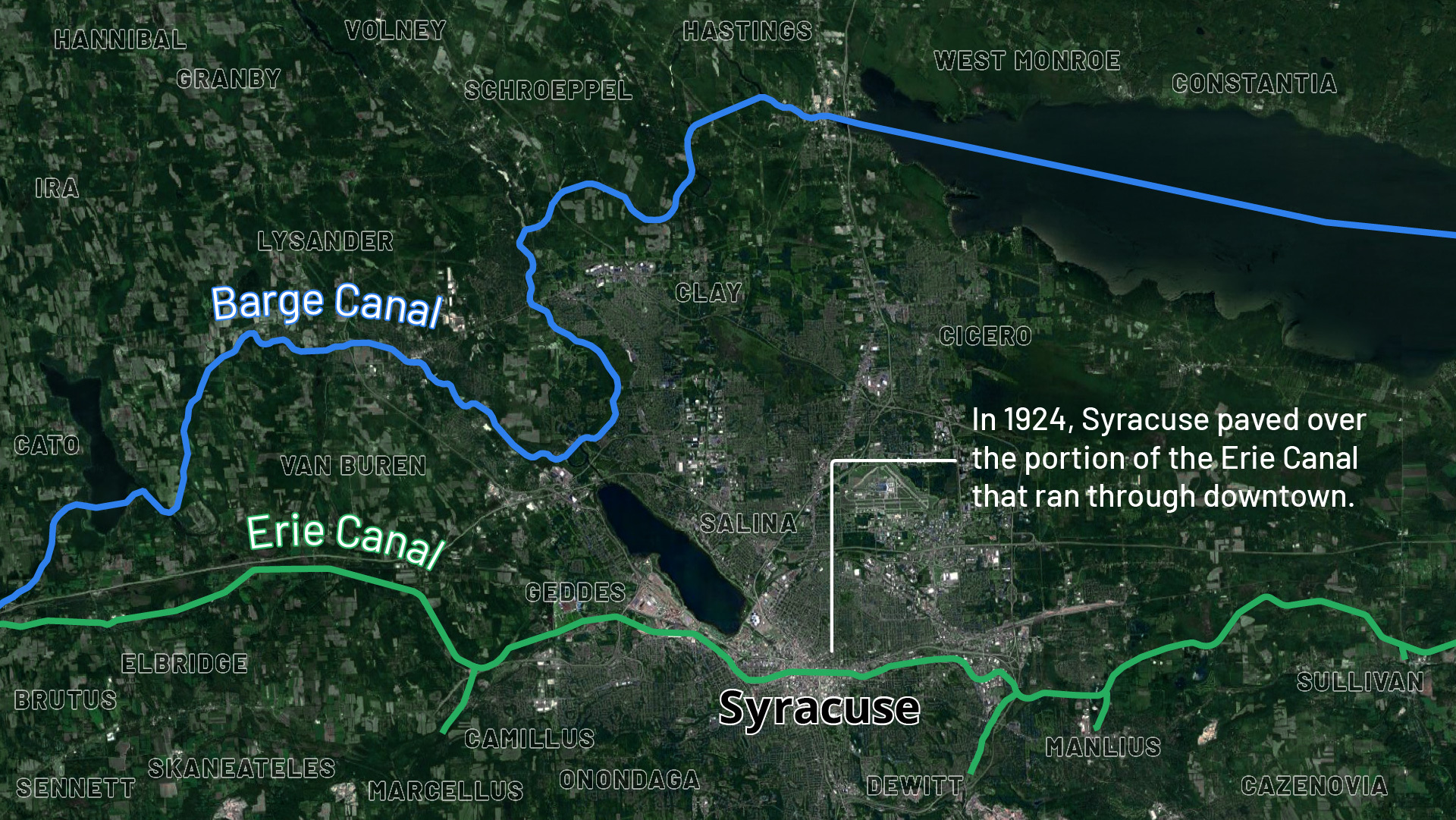

In 1918, the construction of the Barge Canal was completed, making stretches of the Erie Canal irrelevant. Train transit and cargo would also surpass the Canal system in capacity and use in the early 20th century. Syracuse would pave over the Erie Canal in 1924, killing the very thing that gave the city life a year before it turned 100.

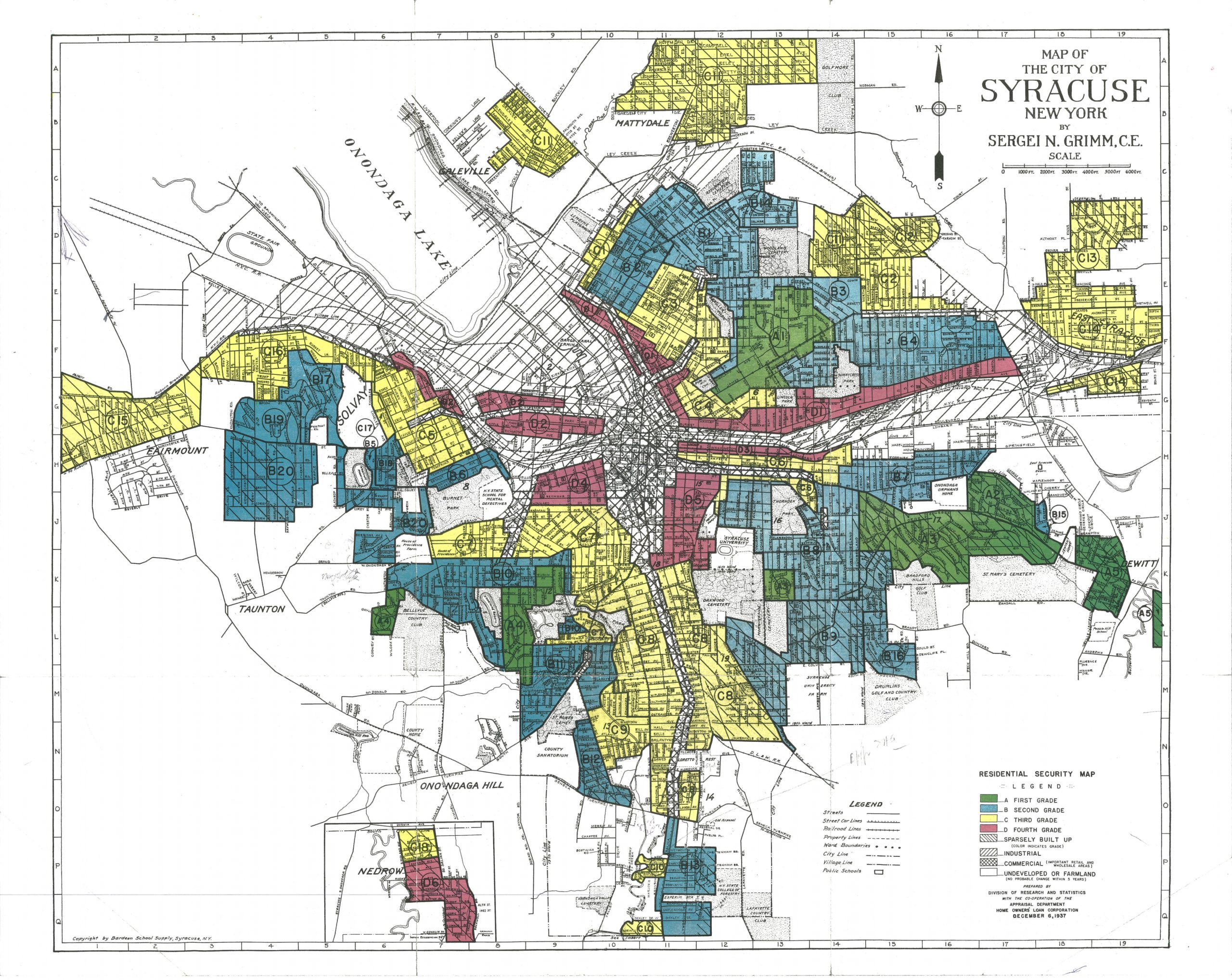

Despite paving over the Canal and removing railroads from the city in 1936, Syracuse could not erase the inequality the infrastructure had perpetuated. Racism and segregation were ingrained in the city and the nation, as the Federal Housing Administration employed policies that “federally sponsored redlining.”

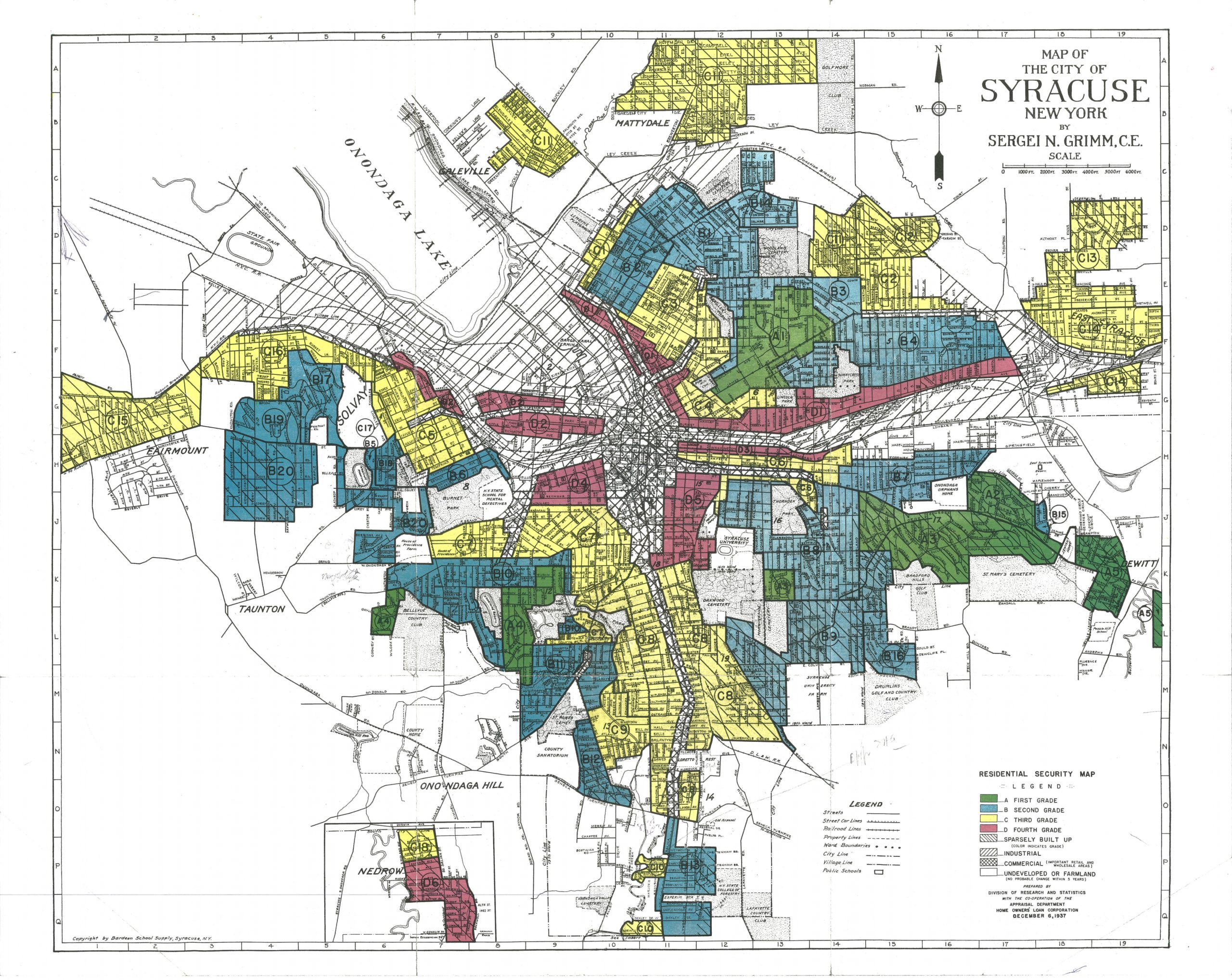

Seen in the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation map of 1937, Syracuse was very successful in continuing the segregation it enforced in 1919.

The red areas were designated for populations that were not economically sound to give loans to, which almost exclusively referred to Black people. The Federal Housing Administration explicitly recommended prohibiting “the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended,” according to the Federal Reserve History website.

And as the Black population in Syracuse grew, that “widespread discrimination led to their almost exclusive concentration in the 15th Ward,” writes OHA, the county historical association. A major part of this ward is labeled as a “D” — meaning the area was labeled as hazardous, denying the residents access to loans that could be used to improve the dilapidation in the area — in the 1937 HOLC map.

City Survey Files

The 1937 HOLC map depicting the redlining zones in Syracuse. The areas in red, largely populated by Black Syracusians, were areas deemed to be high risk, meaning less loan money was given out in those areas.

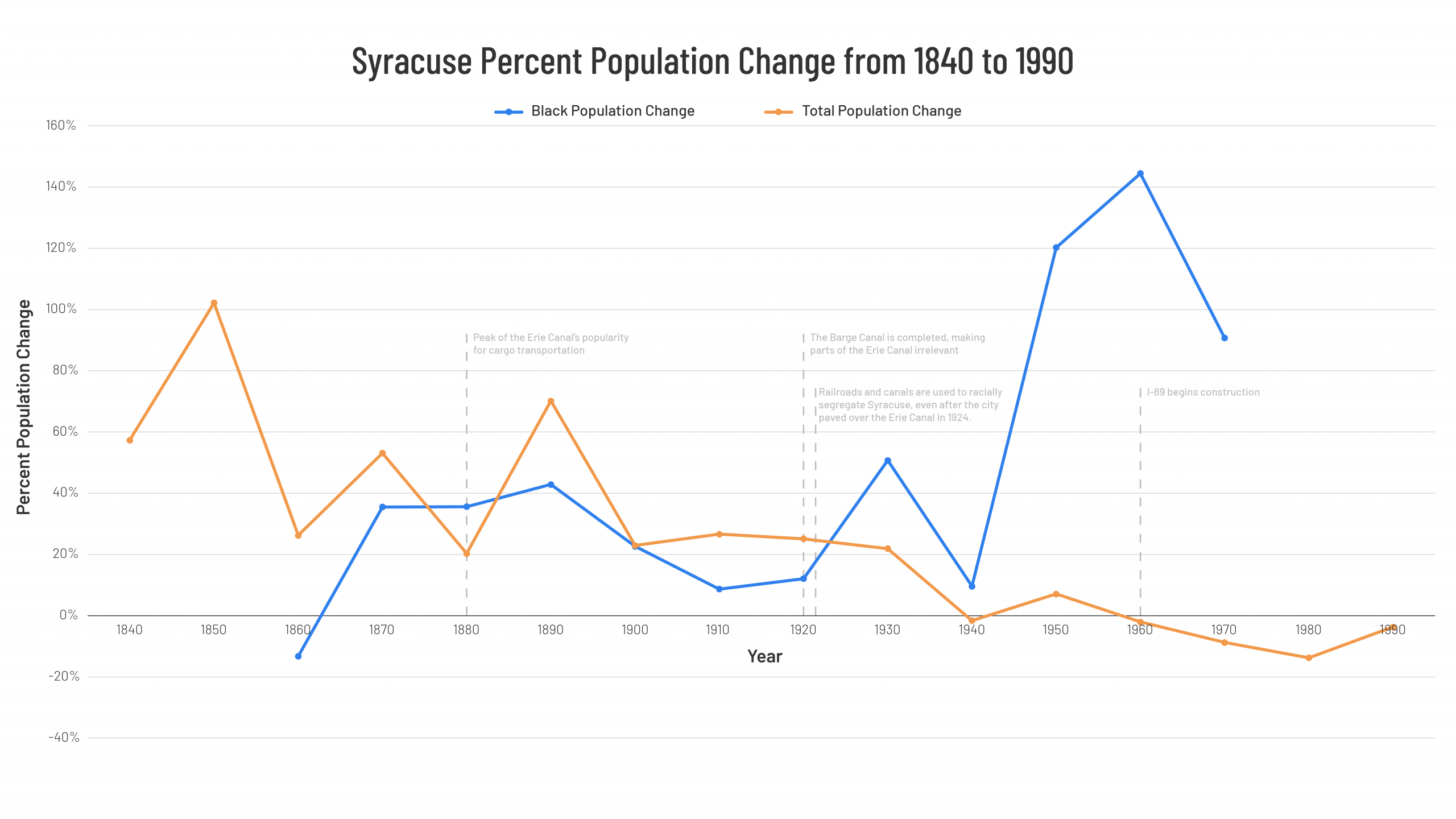

From 1940 to 1950, the Black population doubled from 2,082 to 4,586, and “in 1950, almost 4,000 African-Americans, eight of every nine in Syracuse” lived in Ward 15, according to OHA. By 1960, the city’s Black population nearly tripled, jumping to 11,210.

The Cycle of Infrastructure Begins Anew

During the period of Black population growth, the state wanted to build a highway through the city to continue expanding the networks of highways quickly being built. The pitch for the new infrastructure only strengthened after President Eishenhower’s Federal-Aid Highway Act. But the act held stipulations, writes David Rubin, requiring that “new roads had to be either elevated or depressed if they went through the city.”

And one part of the city made the most sense to demolish for constructing the highway.

“Highways are built through Black neighborhoods because it’s easier to justify politically going through a high-poverty, segregated space,” Rebmann said.

Because of eminent domain – which requires fair compensation for taking private land for public use – the cheapest area to buy out would be the 15th Ward. The poverty exacerbated by redlining also strengthened the justification to demolish the 15th Ward and build I-81.

Despite the state using the cheap land value to justify the destruction of the 15th Ward, the Black community was flourishing in the one place it had been allowed to live. The ward was the heart of the Black community in Syracuse; it had homes, businesses, churches and a strong Jewish and immigrant presence.

“Social cohesion was provided by clubs, churches and the Dunbar Center, the most prominent community institution,” said Otey Scruggs, a former professor of history at Syracuse University, according to OHA. “But most of all, the ties that bound rested on the camaraderie that blossomed from knowing virtually everyone in the community.”

The 15th Ward was much more than land to be razed to construct a highway, but the I-81 project would displace 1,300 families who called it home. Ignoring the concerns of the community about to be dissolved, supporters of the highway claimed it would benefit the city, in turn benefiting all of its constituents. But the benefit for those primarily Black families was unclear.

The community tried to protest the demolition of buildings, but the decision had already been made and construction continued.

I-81 razed the 15th Ward, having 75% of the Black community relocated, and subjecting the residents around the highway to not only continued racism and segregation but “disproportionately high rates of asthma and lead poisoning,” writes the New York Focus. All of these factors exacerbated poverty.

In 1959, as I-81 was beginning to be built, nearly 58% of black families in Syracuse made less than $3,000. The federal poverty line for a family of four in 1959 “was $3,100”, and “a modest but adequate budget cost approximately $7,000,” according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Despite wide-ranging social-safety nets coming into effect in the 1960s, Black Syracusans’ poverty rates stayed consistent with the national poverty rates. In 1970, nearly 30% of Black residents were below the poverty line.

On top of the segregation, discrimination and razing of the Black community, this poverty would be further exacerbated by deindustrialization, white flight and the inability to move because of their poverty.

In 2020, more than 35% of Black Syracuse residents lived in poverty, which is more than double the national average for Black families and triple the percentage of white Syracusans in poverty.

“Poverty is concentrated in smaller pockets, and what you see in the city of Syracuse in particular is what you start to refer to as white flight,” Searing said. “The interstate, which was supposed to breathe new life into the urban core, had the exact opposite effect.