Organizing seed preservation, hunting and fishing, foraging, beekeeping, maple tapping, crop rotations and controlled burns — members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy had mastered these techniques centuries before the Erie Canal tore through their homeland. Two centuries later, their enduring practices still nourish them.

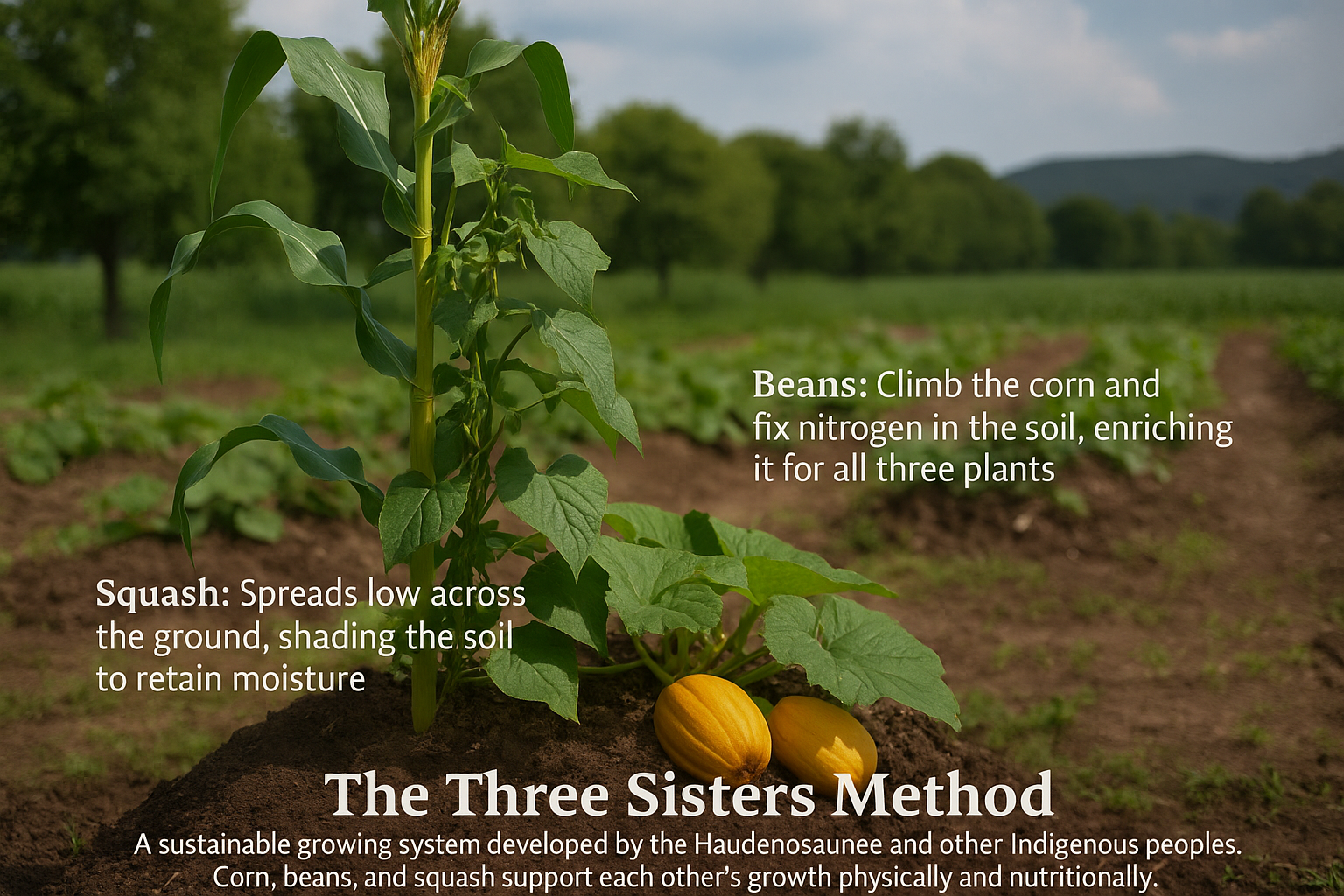

The Onondagas and other Haudenosaunee tribes were the first to farm these lands. They are known for their “three sisters” farming method of planting corn, squash and beans on the same plot. The squash deterred weeds, the corn provided stalks for the beans to climb, and the beans fixed nitrogen into the soil.

But Onondaga Nation Farm Supervisor Angela Ferguson said the Onondagas were diverse in their farming practices beyond the Three Sisters.

“We didn’t always plant Three Sisters mounds,” Ferguson said. “What we were utilizing was more of a crop rotation.”

The farmers would plant crops based on the soil conditions, paying attention to “what we could see was in the soil, or the color of the soil,” Ferguson added.

The Erie Canal, which began construction in 1817, disrupted these practices.

“The Canal represents a giant ditch running all the way across the traditional homelands of the Haudenosaunee,” said Derrick Pratt, Erie Canal Museum educator.

The Canal brought “settler farmers” to the region who, Pratt said, were “stealing, oftentimes, the land indigenous people were using for cultivation or hunting,”

The loss of land changed Haudenosaunee society, Ferguson said, in part by restricting their semi-nomadic style of farming. “We didn’t stay in that same spot for a lifetime,” Ferguson said of the practice. “We didn’t want to over-extract from the soil.”

But the encroachment by European settlers changed “everything,” including “our youth and the way that our children are reared.”

“We had to adapt to what they call ‘reservation,’” she said. “We had always lived in communal homes, and everyone had a role inside of that home. With the establishment of the Erie Canal, we moved more towards individual homes, the way the settlers lived.”

The environmental impact was also devastating, as Canal construction “involves clear-cutting giant swaths of forest — Central New York was almost fully deforested by around 1850,” Pratt said.

Ferguson said that transformation “really affected the biodiversity of what we would see in our waterways and the swamp areas and things like that.”

Despite this, Haudenosaunee influence endures. “We gave them seeds,” Ferguson said. “We showed them how to practice agriculture. We bartered and traded. It was not attributed to Native people.”

Pratt said the Canal played a huge role in the displacement of traditional food and agricultural practices. “You’ve got mostly European-American settlers moving into these areas, bringing with them new farming practices and also disrupting traditional foodways, like hunting,” he said.

Pratt’s Erie Eats project highlighted the Native American food sovereignty movement that Ferguson is pursuing today.

“That includes bringing back historic methods of agriculture and even using historic seeds, because some of these did survive through the generations,” he said.

As the Onondaga Nation farm supervisor, Ferguson is involved in all aspects of her community’s cuisine. But her main focus is on seed preservation.

“You can’t have food sovereignty if you don’t have the seeds,” she said. “The seeds kind of came to me — I like to plant. I like to be in the garden. I like to braid corn. I like to grow all my own foods. That’s my thing.”

Ferguson is at the heart of a Native food sovereignty movement. She shares that knowledge with others: through talks, workshops, indigenous meals, board work and collaboration with museums, botanical gardens and Native alliances.

“I just do what I’m doing, keeping up the ways of my ancestors,” Ferguson said. “I learn a lot trying to find out some of those things and try to bring back some of the old seeds and the old farming methods and agricultural practices and the old tools that we use, and using clay pots instead of stainless steel cans. Everything that was once part of normal village life, we’re trying to reintroduce it to the people, and it’s been really great.”