The Great Law of Peace is symbolized by a white pine tree, known to the Haudenosaunee as the Great Tree of Peace. Arnold said the symbolism of the tree functions to honor the warriors who made a commitment to peace by relinquishing their weapons of war.

“Those weapons were swept away in an underground stream at Onondaga Lake,” Arnold said. “The great white pine was then replanted and at the top of that great white pine is an Eagle.”

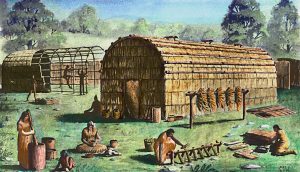

The sacred testament of the lake can be traced back to indigenous cultures that lived and relied on the lake as a main source of food.

Skä•noñh Director Emerson Shenandoah, is a member of the Mohawk Nation who was born and raised on Onondaga Nation land. He reflected on the degradation of the lake over the course of the last century, as overfishing and then pollution depleted local delicacies like shellfish and White fish.

“The lake is very important to us,” Shenandoah said. “If you can imagine, before there were refrigerators and electricity and things like that, the lake was our refrigerator.”

Eagles are also important, Shenandoah said, and eagles’ feathers are symbolic.

“They’re the strongest,” Shenandoah said of the eagle. “We use its feathers to signify what nation we are from in our gustoweh,” a traditional headpiece that symbolizes identity. “The eagle feathers are the ones that we used to show what nation we are.”

Now, local photographers spend hours capturing eagles fishing for food, whose feathers are a prominent symbol in many indigenous cultures.

“The eagle is an intermediary between human beings and the sky world or the creator, so the return of the eagle actually was very profound,” said Philip Arnold, founder of the center and a Syracuse University professor.

Arnold said that his initial motivation in getting involved with the center was due to his wife and two children being Haudenosaunee. He then took the opportunity to work with educational institutions as well as the Onondaga Nation to reform and decolonize the message of the Skä•noñh Center.

The lake, once a source of food for many, became a Superfund site in 1994, said Charles Driscoll, a Syracuse University professor in the College of Engineering and Computer Science.

Driscoll said that there were two main sources of pollution of the lake: nutrients from sewage and heavy metals from industry. The first comes from the county’s sewage treatment plant and the untreated sewage spills into the lake via Onondaga Creek during rainstorms from the city’s overwhelmed storm pipes. The sewage treatment plant itself accounted for 20% of the flow into the lake, the largest flow from a sewage treatment plant into a body of water in the United States, Driscoll said.

The second source of pollution was the industries that ringed the lake, specifically the Solvay Process Company and its eventual parent company, Allied Chemical. The lake became a popular site for industry in part because the Barge Canal, an updated and more robust version of the Erie Canal that was completed in 1918, cut right through the lake.

“The effort was made in the ’90s to improve the wastewater treatment plant to remove the pollutants and nutrients,” Driscoll said. “That was quite successful. There were very large decreases in both nitrogen and phosphorus.”

Then, work began to clean up industrial pollution. “It was a very comprehensive effort,” Driscoll said. “They removed the soil around the industrial contamination and removed very, very large quantities of mercury that had been left on this site.”

Maddi Jane Brown

Eagles’ diets vary and sometimes include the ducks they share the lake with. This has raised concerns about the eagles’ health because of the outbreak of bird flu in the United States.

Driscoll called the cleanup efforts successful and noted that the lake has not been classified as a Superfund site since 2014. But he said that many people still avoid fishing in the lake due to concerns of high concentrations of mercury, and he acknowledges that the cleanup has not returned the lake to the pristine state that local tribes, like the Onondagas, have demanded.

“I sympathize with the Onondagas – that the lake isn’t like it was back in the day,” Driscoll said.

But he celebrates that the lake is now an asset again rather than a liability. “I think people are going out there,” Driscoll said. “There are trails all around the lake, if people want to walk or bike or whatever, and you can catch the fish, and pretty soon, I think it’ll be safe enough to eat the fish.”

Arnold says there is a disconnect between how governments see the lake and the role it plays for members of the Onondaga Nation and the rest of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The confederacy attributes its founding to when the Peacemaker brought the five original nations of the confederacy together on the shores of the lake and laid out the Great Law of Peace, which included democratic practices that would later be an inspiration for Benjamin Franklin and other founding fathers.

“New York state, or Onondaga County, does not feel the same about Onondaga Lake as the Haudenosaunee or the Onondaga Nation,” Arnold said. “The Onondaga Nation feels that the lake is not being cleaned up enough. They’re concerned about the eagles getting sick from polluted fish, so they want it cleaned up and completely restored.”

Shenandoah encourages people to learn about the history of the cultures and land that is now called “Syracuse.”

“South Salina itself, all the way from the lake’s edge to the nation, is supposed to be on Onondaga nation territory, according to treaties,” Shenandoah said. “ I would have people take the time to learn about these treaties and these promises and relationships that the United States government created with my people, and then see how they have been carried on. They’re not necessarily being followed.”