Massive cargo ships carrying tons of coal, produce and other goods float across upstate New York. Their containers stacked as high as Rochester’s historic Powers building and the New York state capitol building in Albany. The Panama Canal-style cargo ships create and support a flurry of new industries, reviving the Canal corridor and its cities, which had been in decline since the smaller Canal had become too shallow and narrow to handle modern ships.

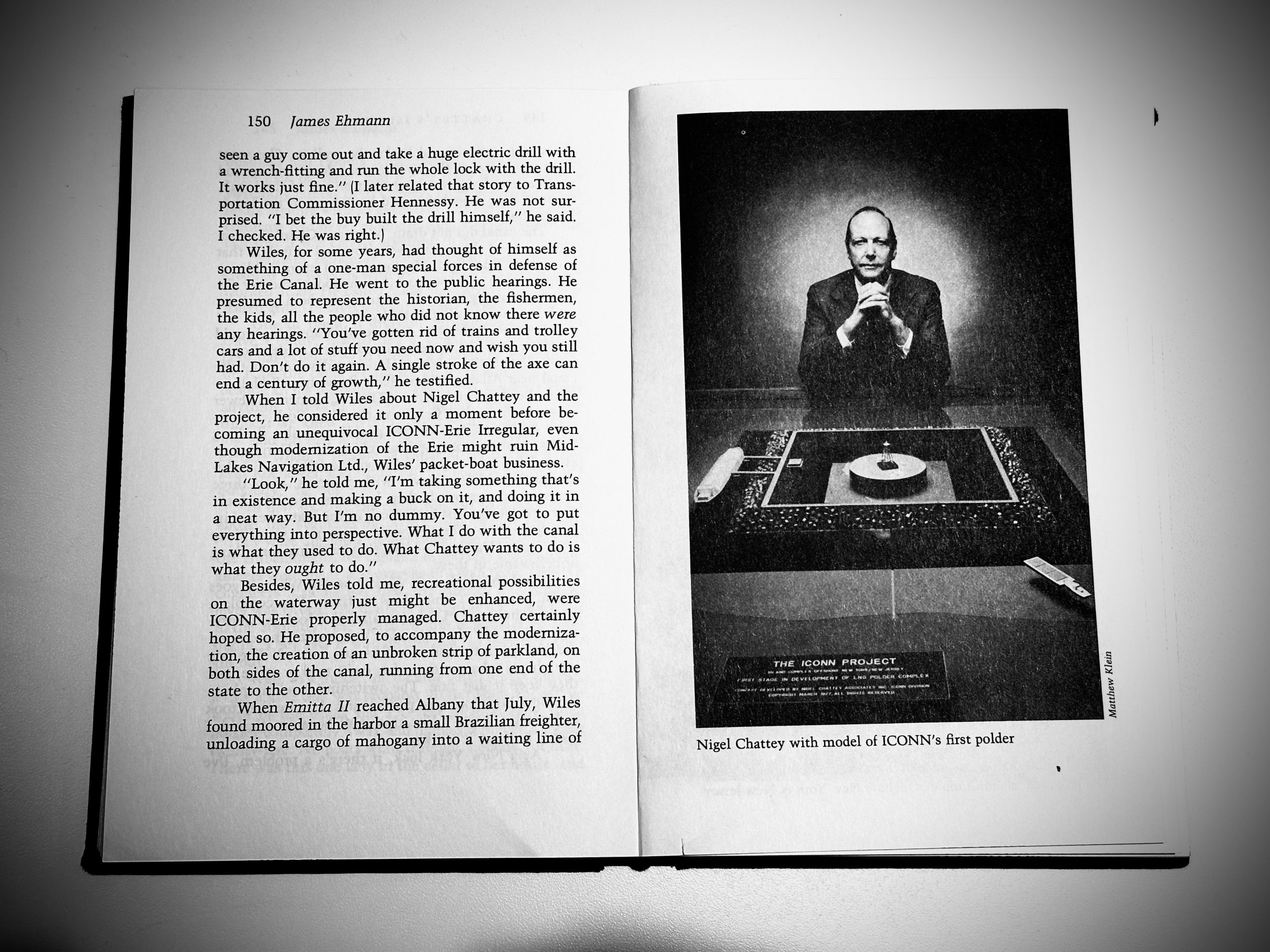

This vision of a modern barge canal never materialized. But in the 1970s and ’80s, a New York businessman proposed just such a project, dubbing it ICONN-Erie and pitching it to elected officials, labor leaders and others.

“It was an outstanding project,” said Jack Webb, a former operating engineer and union leader who was pitched the ICONN project, which stands for Island Complex Offshore New York and New Jersey.

The overhauling of the Erie Canal was one part of the massive ICONN project, which also wanted to build a floating industrial platform in New York harbor that would house an oil refinery, a coal gasification plant, and a garbage dump, connecting those assets to the canal system while keeping them off-shore.

The project might have reinvigorated industries in New York state, but likely would have been massively disruptive. It never came to fruition.

Buzz about the project would begin in the late 1970s as Nigel Chattey would begin to pitch America’s energy production oasis of the future, according to James Ehmann in his book Chattey’s Island.

Chattey grew up in the United Kingdom before becoming a “cavalryman” for Britain in Pakistan, according to Ehmann. After his stint in the army, Chattey would come to America to study at Dartmouth University before dropping out and enrolling at Stanford University. He became an oil prospector after graduation, then worked in the federal government before starting his manifestation of destiny by pitching the ICONN and ICONN-Erie projects to the New York state government.

“You heard Nigel talk, and you really got involved because he was a very personal person,” Webb said. “He put it out there and you went ‘wow, got to go for this baby.’”

The project consisted of two parts, a floating energy island and the deepening and widening of the Erie Canal.

The floating energy island was designed to make use of America’s coal reserves, which couldn’t be burned cleanly due to their high sulfur content, Ehmann said of Chattey’s thinking.

But if the coal could be refined without affecting air-quality on land, it would increase U.S. energy production and lessen the country’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil, and an increase in native energy production.

Policy makers were keen to entertain such approaches in the wake of the Iranian Revolution that helped spark the 1979 energy crisis in the United States.

The man-made island was to be anywhere between 8 and 25-square miles. Manhattan is roughly 22-square miles.

The Clean Air Act had been passed a few years earlier with an amendment coming in 1977, so new power plants and refineries faced more stringent codes to build and operate. The island’s purpose was to try to combat this by being offshore and having winds blow in only 50% of the time, according to a feasibility study by Syracuse University.

On top of the air quality, the floating island could act as a place to dump, store or burn toxic or non-toxic waste.

The other half of the project was to enlarge the Barge-Erie Canal to accommodate barge ships, similar to the Panama Canal, according to company documents. This new super canal could have expanded the entire Erie Canal, or would have been routed up the Oswego Canal to Lake Ontario.

Increasing the size of the Canal was meant to create an easy path for coal reserves from the east coast (in places like West Virginia and the Carolinas) and the west (in states like Montana) to make it to the ICONN complex for refinery and energy production.

It would have the added benefit of being able to aid in the transportation of the massive amounts of produce from the Great Plains to the rest of the world.

Webb said it was both feasible and environmentally conscious, as the dredging of the land would’ve been along the already established canalways, minimizing the ecological damage.

Chattey’s plan, on top of the transportation and energy benefits, would also generate a large number of permanent jobs: 27,000 combined in New Jersey, New York and Connecticut, by his estimate.

These figures don’t include the 7,500 temporary construction jobs and the thousands of jobs that would come as part of a rejuvenation of upstate New York.

Chattey also estimated that there would be $3.2 billion in added value to the region’s private sectors.

Chattey had pitched the project for years, leading to some political support. Former New York state Gov. Hugh Carey called ICONN a “very worthy project,” according to The Post-Standard.

The ICONN-Erie “could, by itself, dramatically improve our economic prospects,” said former New York state Gov. Mario Cuomo in 1983, according to The New York Times.

Having two different New York state governors on board — the primary office Chattey needed to convince of the project’s benefits — was a feat in itself.

It seemed like the project, the new Erie Canal and the supposed rejuvenation of upstate New York, might come to fruition.

But, there is no super canal carrying massive cargo ships across the state of New York, nor is there a giant floating energy complex in New York harbor. Few even remember the proposal or Nigel Chattey.

“(The project) just sort of died,” Webb said.

One part of the ICONN’s downfall was its scope and cost. The first stage of the combined projects would cost $10.4 billion, according to Chattey. That’s roughly $35 billion in 2025 when adjusted for inflation.

On top of the cost, politics also doomed the project.

“You got the politics of New York and New Jersey, and they got on it and they killed it,” Webb said.

Multiple times Chattey came close to securing funding for initial feasibility studies, and most of those opportunities fell through, according to Ehmann.

One of the more notable funding opportunities was $150,000 to support one year of Chattey’s work from the New York state Department of Energy, according to Ehmann. This would also give Chattey an office to work in, but everything produced in the office would be property of the New York state government.

That last clause made Chattey split, as he thought the government would steal his work and not allow him to help oversee the continuation of the project beyond the first year, according to Ehmann.

This reveals one of the biggest — if not the biggest — downfalls of the project: Nigel Chattey himself.

“He was a very good man,” Webb said. “He had good ideas. But for some reason, they never flew.”

Chattey pitched his project to state and federal entities relentlessly and one some converts, but not enough to make the project a reality. According to Ehmann, this was largely due to Chattey’s intense, combative disposition, fueled by an arrogance that clashed with government officials.

Chattey had a few supporters, notably the vice president of a struggling bank located along the Canal Corridor and a higher up in the state Department of Energy. But that wasn’t enough to break past the iron wall of bureaucracy and the coarse political landscape.

So ICONN and ICONN-ERIE remain as “what ifs?” They’re an alternate reality where cargo ships rise 200-feet into the air, competing with upstate’s tallest buildings, allowing upstate cities to regain their prominence as industrial powerhouses.

Or maybe the state avoided a boondoggle, investing billions into a project that would stall, similar to many other languishing mega-infrastructure projects that rack up debt and fail to deliver on their promise.

Whatever the outcome of the massive infrastructure project would have been, all that remains are a few news articles and Ehmann’s book detailing the failings of the ICONN projects and their visionary.

“It’s the way things go,” Webb said. “Things change and we get older.”