As a child, she watched and learned from her aunt, a quilter by profession, and her grandmother, who made clothes for Homer’s children. She credited her aunt for giving her the courage to launch Homer Couture — a dream that had been a decade in the making.

“When I was talking to her about fashion and coming up with Homer Couture, she was like, ‘You know what? Just do it,’” Homer said about her aunt’s advice. “Because in 20 years, you can tell the kids, ‘Hey, you know what? I tried. I did what I wanted to do.’ I’m glad she did that. She gave me that push to go after it.”

Since then, 43-year-old Homer has enlisted the help of several other Indigenous fashion and beauty professionals, including Jessica Tarbell, a member of the Mohawk Nation and owner of Black Wolf Esthetics and Lash. Tarbell has handled Indigenous makeup for Homer’s models since her first show at Syracuse Style.

“I like to ask Mary what she’s looking for style-wise, and I play off of what she’s looking for so each show can be a little bit different,” Tarbell said.

Tarbell also emphasized their desire for inclusivity in Indigenous makeup: different tribes have various styles of makeup with specific meanings, and it is important to maintain their distinctiveness while mixing them. She explained that members of the Iroquois Confederacy in New York aren’t “really flashy” and keep makeup to a minimum. But tribes from the western United States incorporate a face dot and other markings into their makeup.

“I feel like whether it’s me being a Mohawk or somebody out West, I want to show our heritage,” Tarbell said. “Our people are Indigenous, so (we) show it off because we’re proud of it.”

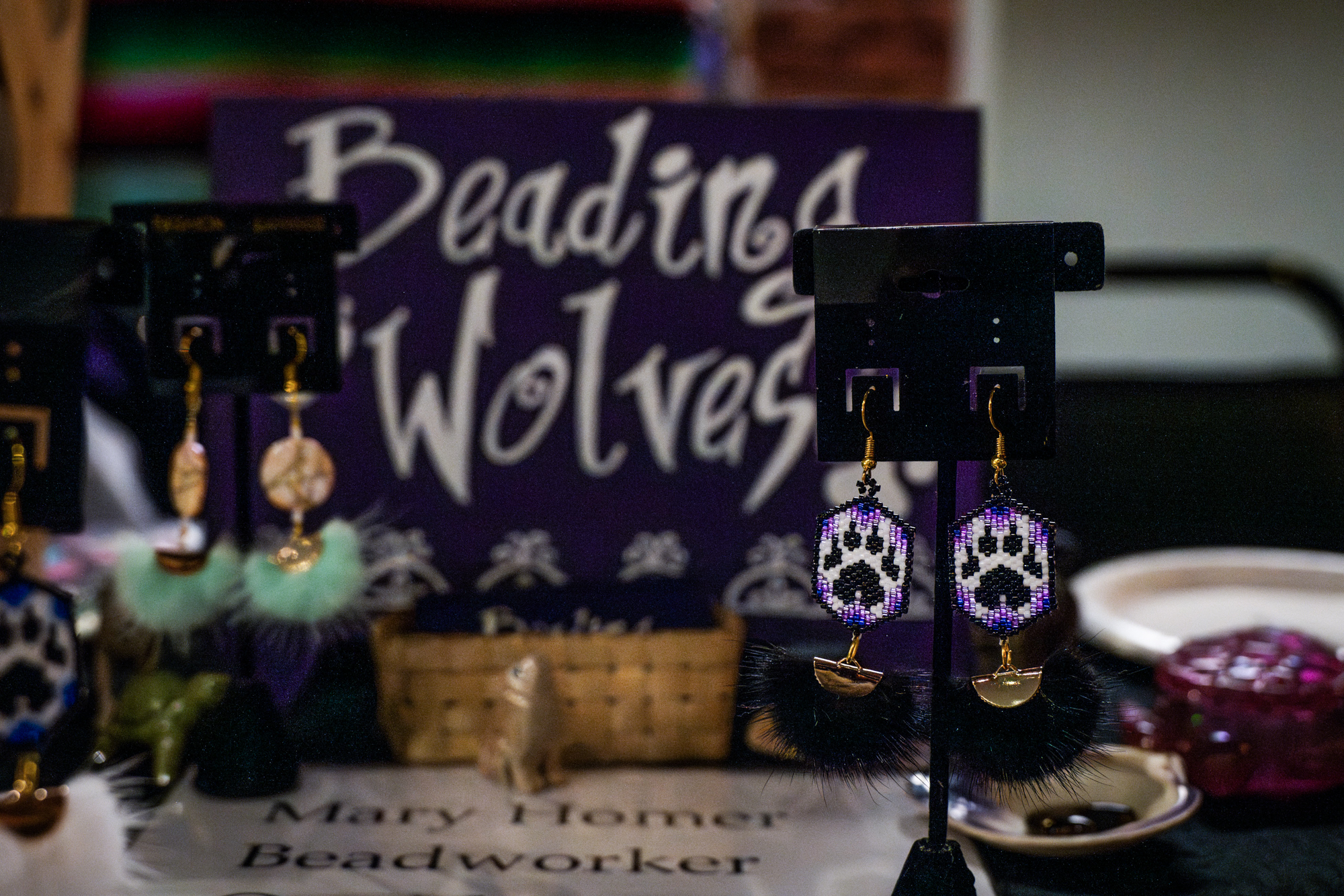

And if running one business wasn’t enough, Homer also makes and sells jewelry under her family-owned beadworking enterprise, Beading Wolves.

Homer was 8 when she started beading with her mother, stringing single-strand necklaces and wrapping dreamcatchers to learn the motion and technique of traditional Oneida beading. She then began experimenting with bugle beads and brick stitching. Before long, she was making multilayered necklaces, intricate earrings, keychains, paracord bracelets and hand-sewn purses.

Beading Wolves was launched in 2004 after Homer’s second child was born. The enterprise’s name aligns with the Wolf Clan’s matrilineal society.

Holly Gibson-Orcutt, Homer’s cousin and collaborator for Beading Wolves, helped translate the Oneida words, meaning “those three or more ladies of the Wolf Clan sew the beads down,” as an homage to Homer and three of her daughters, who are also adept at beading.

And at the 2024 Syracuse Style show, Homer’s two worlds – beading and sewing – converged.

“I’ve always loved to do beadwork, but I’ve always loved watching fashion,” she said. “And I’m like, ‘Why don’t they put beads on the dress? Why aren’t they putting beads on the shirt? Why aren’t they wearing ribbons?’ We need more Indigenous representation in fashion.”