In downtown Rochester, on Corinthian Street behind the Reynolds Arcade, lies the historical site of Corinthian Hall, a prominent space for concerts, plays and speeches in the 1800s. The grand hall welcomed notable figures from 19th-century movements like Susan B. Anthony, Frederick Douglass and the Fox Sisters before a fire destroyed the building in 1898.

Today, a parking area for the Holiday Inn hotel occupies the site where Corinthian Hall once stood. The location borders the Genesee River and an aqueduct from the original Erie Canal that was constructed in 1825. The lapsed historical site is among the landscapes that Rochester native Clara Riedlinger is spotlighting through the 2024-25 Erie Canal Artists-in-Residence.

As a fine art and documentary photographer, Riedlinger is dedicating her project to capturing the unique spiritual history of western New York driven by the Erie Canal. She hopes her work will bring awareness to canal landscapes rich in history, which community members may pass without realizing.

“There are a lot of things that get lost in history, but it’s still there,” Riedlinger said. “I had been interested in the supernatural and spiritual history of the landscape for a long time, but I thought it was too weird. Then the residency program came along, and it was a perfect fit.”

The Erie Canal transformed New York State in more ways than one, allowing for the exploration and quick travel of ideas. Riedlinger’s interest in the religious strangeness tied to the Canal began with the Fox Sisters, who played an important role in the birth of modern Spiritualism in the Genesee Valley.

“As soon as I heard the story of the Fox Sisters, I latched onto it immediately. I was entranced by them,” she said.

Two of the sisters, Leah and Kate, reported hearing ominous thuds and cracks in their family cottage in the hamlet of Hydesville that they described as “raps.” The girls believed that the sounds were coming from a peddler who had been murdered and was buried in their basement. After claiming they could communicate with the dead, the sisters began offering séances for one dollar, managed by their eldest sister, Maggie.

After their first public séance at Corinthian Hall in 1849, word of the girls’ powers traveled quickly, leading them to perform séances across the country. Maggie later publicly claimed that their spiritual powers were a ruse, admitting that they produced the rappings by flexing their toe joints with little movement.

“The idea that these girls could affect everyone’s perception of reality really gnawed at me,” Riedlinger said. “These girls, who otherwise had no voice over their own lives, totally took charge of themselves.”

Figures like the Fox Sisters exemplify the intersection of religion, gender and justice movements in American culture. Modern Spiritualism challenged traditional norms, as the movement was largely led by women who took on central public roles as mediums.

Whether or not the Fox Sisters could truly communicate with the dead may remain a mystery, but their impact is steadfast. In 1904, human remains of the peddler who started it all were discovered in the crumbling foundation of the sisters’ Hydesville home.

Throughout her residency, Riedlinger visited and photographed many sites of historical significance, like the remaining foundation of the Fox Sisters’ home at the Hydesville Memorial Park, the site of Corinthian Hall and Hill Cumorah, where Joseph Smith Jr. discovered the gold plates containing the translations for the Book of Mormon.

Reimagining the Erie Canal

The NY Canal Corporation and the Syracuse Erie Canal Museum launched the Artist-in-Residence program in March 2023 through the Reimagine the Canal initiative. Now entering its third year, the initiative supports economic development projects for canal communities.

“Reimagine the Canal is about seeing the Erie Canal in a new way and revitalizing it for the 21st century, and art is a big part of that,” said Angelyn Chandler, vice president of planning for the New York Power Authority.

Riedlinger says the canal corporation has been supportive of the “weirdness” of her project, giving her the confidence to unapologetically pursue her vision: “The support has allowed me to produce high-quality images that really underscore the ideas that I want to explore.”

Chandler noted that Riedlinger’s contributions are especially valuable because religious and spiritual movements are not prioritized in traditional narratives of the Erie Canal, which focus primarily on economic expansion.

“Artists have an amazing power to have a different perspective on something that will catalyze everyone to look at it in a different way,” Chandler said. “I hope this project makes people who have the Erie Canal in their backyard take another look and realize there’s more to it.”

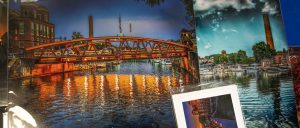

Riedlinger’s creative process, which she describes as meditative, begins with background research about the oddities of the Erie Canal. She typically photographs sites alone, around sunrise or sunset, to take advantage of the natural lighting.

“I find myself in some extremely beautiful and mysterious locations that I’m really grateful to find,” Riedlinger said.

She is particularly interested in capturing nonlinear time, an idea she says many people struggle to understand.

“There are certain places where you can exist through multiple eras of time and look through the eyes of someone who lived there in the 1800s,” she said. “It’s difficult to verbalize bodily and spiritual experiences. You just have to feel them to understand.”

By the completion of the program, Riedlinger presented about a dozen images supporting her theme of spiritual history and its connection to the landscape in the past and present, reflecting a year’s worth of research and fieldwork.

Leading up to the 2025 bicentennial of the Erie Canal, Riedlinger hosted public presentations of her documentary photography at the Oneida Community Mansion House and the George Eastman Museum, plus the At Water’s Edge: Reflections on 200 Years of the Erie Canal exhibition at Syracuse’s Everson Museum of Art.

“I hope that viewers walk away with a more enchanted worldview,” Riedlinger said about her photography. “My photos have an enchanting and otherworldly realm about them. I hope that opens people up to the possibility that there’s some magic left in the world.”

Early inspirations and related works

Clara’s father, Michael Riedlinger, introduced her to photography and camera equipment at a young age. He gifted her a 1970s Canon F1 camera when she was a child – a camera she still uses today.

“I’ve been a photographer most of my life,” she said. “I was 6 or 7 when I first started shooting photography. It’s always been a part of my life and how I interact with the world.”

In addition to Riedlinger’s primary medium of photography, she also produces documentaries and fiction films. She teaches film production at the Rochester Institute of Technology, where she earned a master of fine arts degree in film production in 2021. She completed her undergraduate studies in film, video and sound art at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 2016.

“Filmmaking is a huge part of my practice,” she said. “I approach both filmmaking and photography with a similar mindset and style. I want them to be cohesive together.”

Riedlinger’s personal interests and artistic endeavors have come together in the realm of traditional folk music. A fiddle and guitar player herself, she has collaborated with other folk musicians on music videos.

“Give the Fiddler a Dram,” for example, is a music video Riedlinger produced for the Old-Time Tiki Parlour, a concert and workshop space in Los Angeles created by David Bragger. The video features Bragger, Susan Platz, Howard Rains and Tricia Spencer performing the ballad in a church balcony, filmed during a fiddle camp in Mars Hill, N.C.

Riedlinger focuses her work locally by filming artists in central New York. Riedlinger recently produced a music video for the Grady Girls, a traditional Irish band based out of Ithaca that she has watched perform since she was a teenager.

While her artwork and photography have long carried common themes, Riedlinger says her work continues to evolve over time.

“I’ve become more confident that I have something interesting to say through my photography. I don’t feel like I have to ask permission to explore the ideas that I want to.”