In 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings set out on a mission to prove they were the best baseball team in the United States.

After sweeping their home games in May, baseball’s first-ever professional team ventured out of Ohio for a 22-game June tour across the Northeast.

The Red Stockings’ schedule included the country’s biggest cities: Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Washington, D.C. – cities that still have Major League Baseball teams today.

But before arriving in those cities, the Red Stockings started their journey in New York.

Over a week, Cincinnati made stops in Buffalo, Rochester, Troy and Albany to face clubs in each of the Erie Canal cities – essentially putting Upstate New York baseball on the map.

Cincinnati insisted on playing “the finest nines,” which meant a team had to be a formidable opponent. While the Troy Haymakers was the only professional team in the region, the Red Stockings felt the up-and-coming Buffalo Bisons, Syracuse Central Citys, Albany Nationals and Rochester Alerts had enough talent to schedule a game.

The Syracuse games were rained out and made up that August in Ohio, while the three other Canal-based teams fell short against the Red Stockings during a season that would see some controversy.

Upstate New York’s interest in the then-emerging sport of baseball in the late 1800s coincided with the influx of people and wealth during the Canal’s heyday. Along with several pro teams across the region, the Canal cities all have significant ties to baseball’s early days, from future Hall of Famers to innovative business practices.

In 1860, Buffalo became the 10th largest city in the United States and grew to the eighth largest by 1900. Albany, Rochester, Syracuse and Troy cracked the top 30 in the 1870 census, with populations of over 43,000 each. Major cities have shifted over the past 150 years, Baltimore and Milwaukee were the 30th and 31st largest cities according to the 2020 census, and both have current MLB teams.

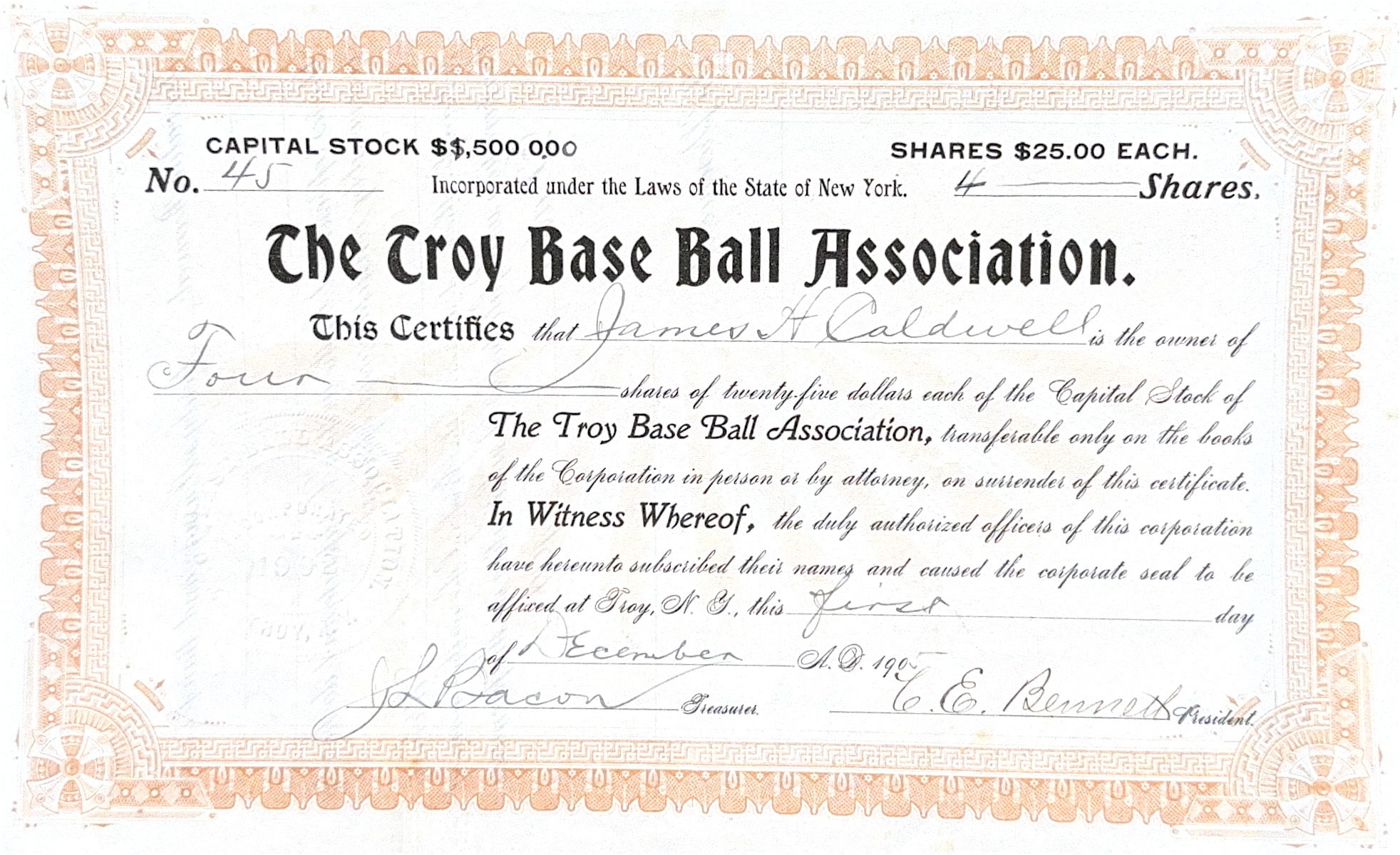

Located at the intersection of the Canal and the Hudson River, Troy became an industrial hub. In 1840, Troy was the fourth-wealthiest per capita city in the country and the second-leading producer of iron.

“All of this industrial activity in the 1860s and 1870s helped create a working class in Troy that had sufficient capital and leisure to spend on amusements, including baseball,” Jeffrey Lang wrote in his book “The Haymakers, Unions and Trojans of Troy, New York.”

Baseball grew rapidly in the 1800s. Leagues like the American Association and National Association vied for “major league” status to compete with the National League. Teams jumped between leagues, hoping to find better competition, lure more fans, or simply survive as a business. While no major league team has called Central New York home in over a century, the teams and individuals left their mark in the early years of organized baseball.

Syracuse Stars among earliest teams to integrate

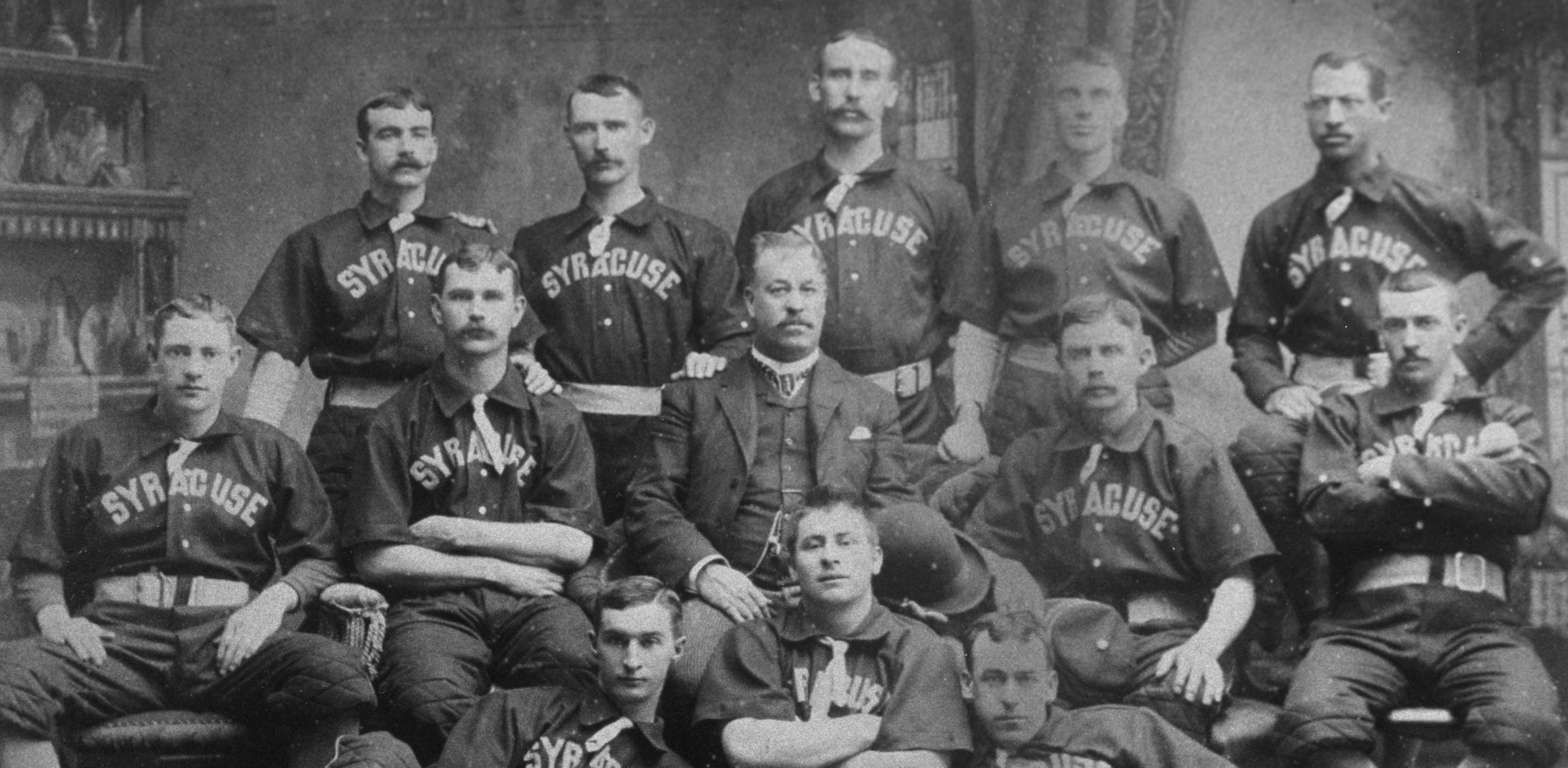

From the beginning of the 1887 International League season, chaos and racial injustice followed the Syracuse Stars.

Before the season started, the team signed seven players from the defunct Southern League located throughout the Southern United States. The Toronto World reported cliques formed within the team.

Manager Joe Gifford resigned on May 21, according to The Sporting News. Gifford could not solve the team’s internal problems and left to manage the Columbus baseball team in Ohio.

The Stars hired Joe Simmons as his replacement. Simmons quickly made moves to turn the team around. One of those moves was to sign Black pitcher Bob Higgins.

Though Higgins was recommended by his Memphis team, his new teammates did not welcome him with open arms.

On May 26, Higgins made his debut on the mound for the Stars during a road game against the Toronto Baseball Club. The Stars lost the game 28-8. Only seven of Toronto’s runs were earned, meaning most were caused by errors and lazy fielding.

The headline for the World read “Disgraceful Baseball,” followed by “The Stars boycott their pitcher in Toronto.”

Despite his team’s awful play in the field, the World reported that Higgins “retained control of his temper and smiled at every move of the clique.”

Tensions within the team did not get better. On June 5, the team met at P.S. Ryder’s gallery for a photo shoot. Pitcher Doug Crothers and left fielder Hank Simon refused to take a photo with Higgins.

Simmons suspended Crothers indefinitely after he refused to join the team photo. Crothers started a fight with Simmons and struck him in the face in a meeting later that day.

Crothers eventually apologized for hitting Simmons, and the team granted his release in July. He stood firm on his decision not to take the photo with Higgins.

“I don’t know as people in the North can appreciate my feelings on the subject,” Crothers said. “I am a Southerner by birth, and I tell you I would have my heart cut out before I would consent to have my picture with that group.”

Higgins had a standout season for the Stars despite the racism he faced from his own team. On the mound, he posted a 20-7 win-loss record with a 2.90 earned run average. He found equal success at the plate, where he finished with a .294 batting average and stole 28 bases.

Higgins’s success gave the Stars plenty of reasons to push back when the International League considered banning Black players. At the league’s off-season meeting in Toronto, the team’s director and president represented the team with the intent to keep the current rules regarding Black players on rosters.

“They will take a firm stand in favor of allowing colored players to enter the lists,” the Syracuse Courier wrote on Nov. 9. “Should they succeed in their efforts, Bob Higgins, the colored phenomena, will sign here at once.”

The Stars succeeded in keeping the league open to Black players, and the team re-signed Higgins. They soon signed another Black player, catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker. The two would form one of the first all-Black pitcher-catcher duos in baseball.

Higgins became a favorite of many fans. The Courier wrote in March 1888 that “Higgins’ colored friends will give him a warm welcome, but not any more so than the one he will receive from the whites.”

Though 1888 was another successful season for him, Higgins did not finish the season in Syracuse. In August, Higgins did not appear when the team left for a trip to Buffalo. According to the Courier, Higgins claimed that his mother was sick and he was anxious to go home. He returned to Memphis and opened up a barbershop.

Despite losing their star pitcher, the Stars won the International League championship in 1888.

The Stars played in multiple minor leagues until 1929, when the team disbanded. The Chiefs brought minor league baseball back to Syracuse in 1934 as an affiliate for the Boston Red Sox.

Since 1961, the Chiefs were affiliated with seven ball clubs before rebranding and becoming the Syracuse Mets in 2019 to coincide with their affiliation with the New York Mets.

Buffalo Professional Baseball Club

Baseball was present in Buffalo as early as 1857, when amateur clubs traveled locally to play one another in informal leagues. The Niagaras found early success from 1857 to 1871 and laid the foundation for the city’s rich history of professional baseball.

Following a six-year void with no official baseball teams in Buffalo, a group of local investors created the Buffalo Professional Baseball Club (known as the Buffaloes) in 1877. Professional baseball in Buffalo was wildly successful and nearly granted the Buffaloes a chance to be in the present-day MLB.

The 1877 season was an unremarkable one, with the team only winning 10 of its 40 games. They also cut their best pitcher Larry Corcoran, seemingly because he was too good.

“His pitches are so swift no catcher can hold him,” Billy Barnie, the Buffaloes’ 25-year-old player-manager said, according to The Seasons of Buffalo Baseball.

But team owners were creative when it came to business operations. The Buffaloes had an off-site ticket office, a scoreboard in centerfield and players selling scorecards to fans when not in the lineup.

Despite the lack of success on the field, the owners’ creative approaches helped the team turn a $490.60 profit at a time when teams were looking to break even.

Going into the 1878 season, the Buffaloes fired Barnie even though a local newspaper urged them to give him more control of the team. Business manager George Smith took over the team.

The team had a worrying start with a loss to the London Tecumsehs. But behind the pitching of future Hall of Famer Pud Galvin, the team went 81-32 for the season and won the newly formed International Association’s Pennant.

The Buffaloes winning the pennant gained them a move to the National League, where they finished third out of eight teams in their first season in the majors. That season the name Bisons began to stick, which remains the name of the Buffalo minor league team today.

Led first by Galvin, who would become pro baseball’s first 300-game winner, and later by Dan Brouthers, a first baseman and one of baseball’s first great home run hitters, the Bisons were able to achieve financial stability with a strong roster of players, keeping them in the major leagues for nearly a decade.

After a few seasons in the International League, the Bisons joined the newly formed Western League, which was intent on challenging the National League for major league competition.

But Western League founder Ban Johnson went behind Buffalo’s back and gave the spot to a Boston team that would later become the Red Sox. The people of Buffalo didn’t take kindly to being left out, and they were left feeling like they had been stabbed in the back by Johnson.

The start of the 20th century saw the era of major league baseball end in Buffalo aside from a two-season stint in the upstart Federal League in 1914 and 1915. Buffalo teams would remain in the minor leagues with the Bisons, now the Triple-A affiliate for the Toronto Blue Jays.

Rochester Baseball Club

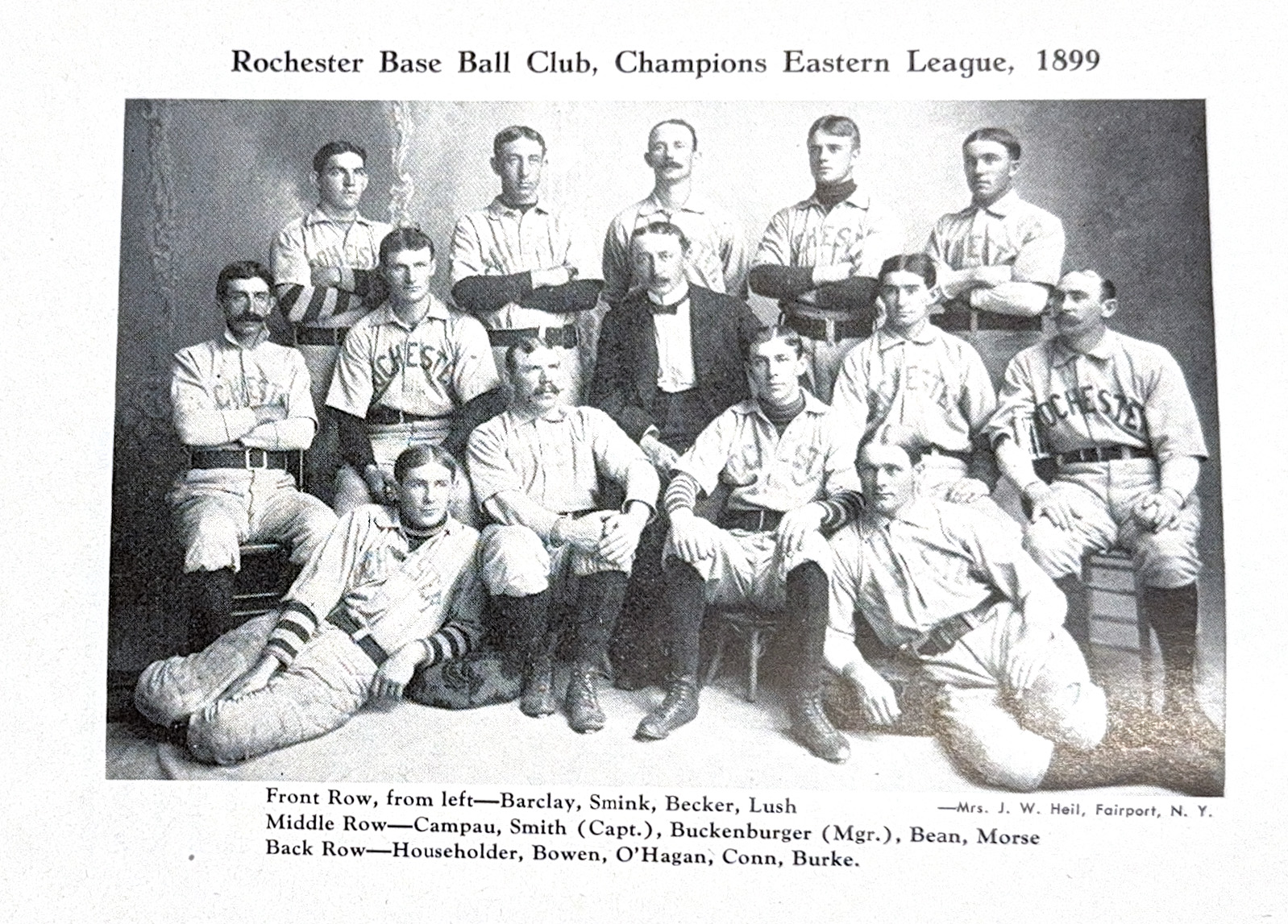

The Rochester Baseball Club is a story of perseverance through bad luck and bad performances.

Similar to Buffalo, Rochester has a rich history of baseball, especially amateur teams. But professional baseball in Rochester wasn’t a constant nor as successful as it was in the Canal city further west.

The first year of professional baseball in Rochester was 1877 with the Rochester Baseball Club, but it lasted only a couple of seasons before the Hop Bitters had their only season in 1880.

Rochester’s home stadium at Culver Field caught fire in 1893, preventing play for two years.

Under new ownership, Rochester won a pennant in 1899 in the Eastern League. New manager Albert Buckenberger led Rochester to another league pennant in 1901.

Despite the success, Rochester’s team became known as “Buck’s Bronchos” because of its dirty play and attitude toward fans and umpires. One player put a hat pin in his mitt, another regularly walked on the toes of opponents and umpires with his cleats, and fistfights were routine between Rochester players.

The team’s reputation overshadowed its ability to win, and in 1904, the newly renamed Beau Brummels went 28-105, becoming one of the worst teams in Rochester baseball history.

Starting in 1929, Rochester’s team became the Red Wings and an affiliate for the St. Louis Cardinals. Today, the Red Wings are the Washington Nationals’ Triple-A affiliate.

Rochester has had a team since 1899, making the current Red Wings one of the oldest teams in baseball.

Controversy in Cincinnati

As for the 1869 Red Stockings that barnstormed New York, knocking off Canal town baseball clubs early in the season, it was the Troy Haymakers that nearly achieved what seemed impossible that year.

At Cincinnati’s home field on August 26, the two teams were tied at 17 after five innings of play with the Red Stockings’ 39-game winning streak on the line.

Cincinnati’s Cal McVey came to the plate to lead off the top of the sixth inning. It appeared that McVey should have been the first out of the inning after a foul tip was caught on the first bounce, which was considered an out at the time.

After umpire John Brockway ruled the ball not caught, Troy’s president Jame McKeon, who had already argued a call earlier in the game, ran onto the field, pulled his team off and left the ballpark in protest.

While the umpire gave Cincinnati the 9-0 forfeit win, the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players declared the game a 17-17 tie. Even though the league ruled the game a tie, Major League Baseball considers the game a win for Cincinnati, which finished the year 57-0.