Leah de Rosa did not expect to find herself on the overgrown banks of the Erie Canal, with the keys to her own business in hand.

De Rosa’s work fills the inside of an unassuming factory on West Fayette Street in Syracuse’s Far Westside neighborhood. A maze of design specs, industrial refrigerators and inventory mark the start of her efforts to create a physical location for her online community farmers market, Plum & Mule — a Canal-inspired name.

“The mules used to carry the packet boats up the Erie Canal, and I wanted this story to (be) our name,” de Rosa said. “This is a historic building, right there where the Erie Canal was.”

The Canal’s legacy continues to shape the culinary identity of central New York, from farmers setting up fruit-and-vegetable stalls along the Canal in the 19th century, to the farm-to-table movement of today. Central New York’s fertile soil, rivers, salt deposits and deep valleys all made the region conducive to farming and transportation, even before the Canal.

“You’ve got the Mohawk River, the primary mode of transportation between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Coast, which is a better passage through the Appalachian Mountains than most,” said Derrick Pratt, Erie Canal Museum educator. “But still, the Mohawk has a lot of rapids and waterfalls, so that resulted in costly and time-consuming needs to carry all your stuff around those obstacles.”

In 1817, the Canal’s construction broke ground in central New York, in part to get around those rapids.

“Where the Canal is built, just the engineering of it, goes through relatively low-lying flat and more fertile parts of the state, rather than the hills to the south,” Pratt said.

The Canal helped the existing salt-harvesting business in Syracuse boom and led to its “Salt City” moniker. “The canals were the big thing that makes the missing link in that formula, in that you can now efficiently transport and cheaply transport salt,” Pratt said.

The Canal also forced upstate New York farmers to diversify their crops in order to compete with farmers settling inland to other parts of the Great Lakes Basin.

“Settlers from the East Coast and a lot of European immigrants — Germans, Scandinavians — they start establishing farms in places like Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, all places with better soil conditions and growing seasons than New York,” said Pratt, who spearheaded the canal museum’s Erie Eats project.

These new, westward farms began challenging the once-dominant New York market.

Anne C. Bellows, director of SU’s nutrition and food studies graduate program, described this shift as “huge in terms of changing options people had in terms of what they planted, what they were able to sell, where they were able to sell it, what people could purchase, more information about diverse farming practices, the movement of labor that supplied support for farms — the whole matter of expanding and changing the food system.”

Local farmers, Pratt said “shift their agricultural focus from wheat to higher-value crops, things like vegetables and fruits, which they grew along its banks.”

But the Canal was also a mover of immigrants and culture: East Coast cities were overwhelmed by the European immigration surge, forcing newer immigrants westward or upstate. Italians, Germans, and Irish brought with them food traditions that became central to Central New York cuisine.

“The salt potato is generally credited to Irish and German immigrants,” Pratt said. “Similarly, beef on weck — that’s largely German.”

Utica staples like chicken riggies and tomato pie were brought by Italian immigrants and the Halfmoon cookie from German immigrants, Pratt said.

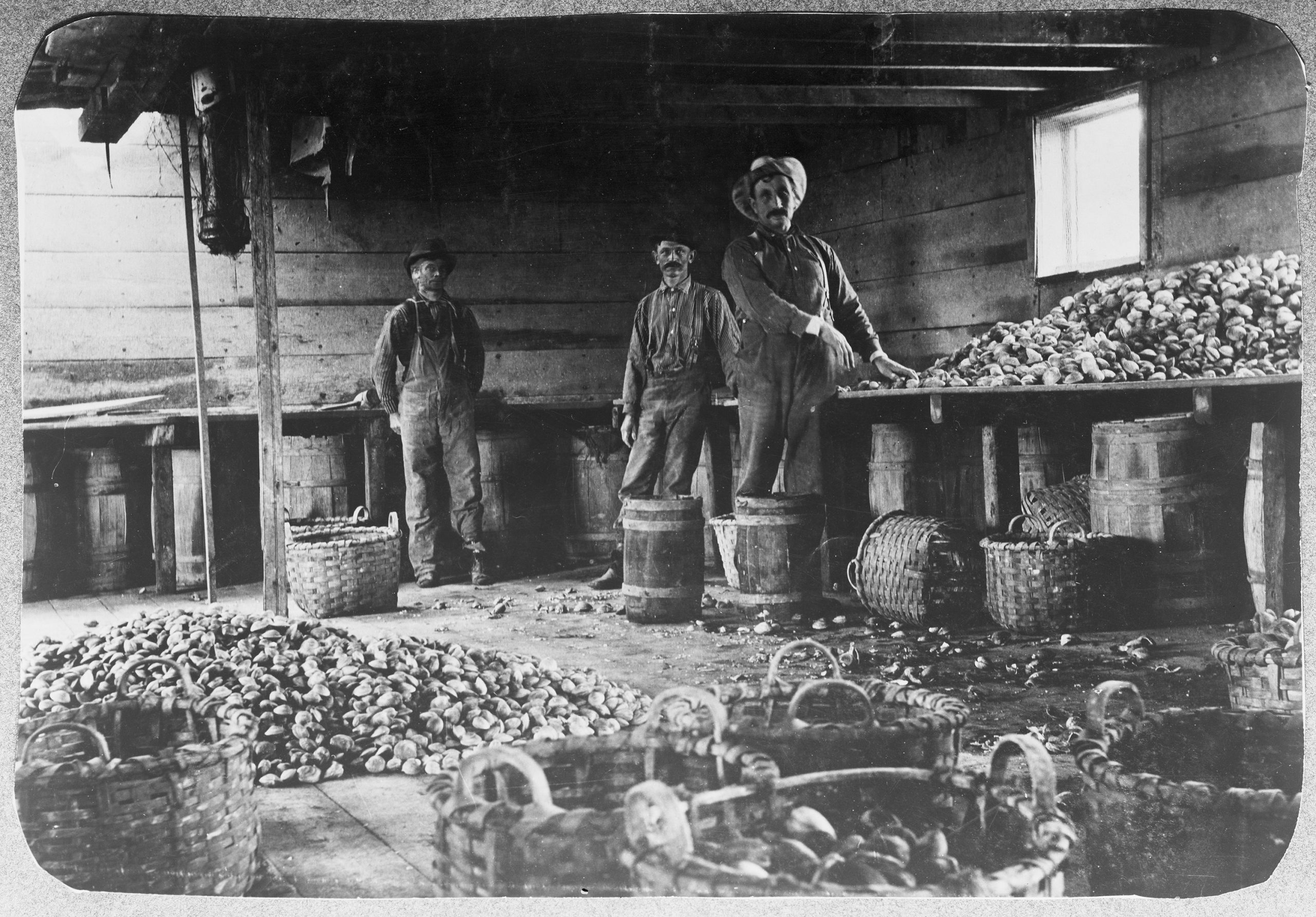

Oysters, native to the Eastern seaboard, became the first Canal “food craze,” now able to reach inland cities fast and cold enough to preserve freshness. Pratt calls this a “feedback loop” — a goods exchange between farms and cities.

“Raw materials and food, especially, are moving down the canal into these growing industrial cities, like New York, and feeding the growing industrial base,” he said. “Cities don’t grow food — it really helps sustain those populations and then manufacture goods, which are then shipped west to all these new farms.”

But the Canal’s dominance began to fade by the late 19th century with the rise of the transcontinental railroad.

“The railroad’s faster,” Pratt said. “If you have relatively nonperishable items, you can put those on a canal boat and it’s cheaper, so a lot of canneries actually formed on the banks.”

To stay viable, the Canal was widened to accommodate larger barges, especially for grain shipments. Still, the changes pushed many small farms out of the market.

“It created larger and larger businesses that push smaller folks out,” Pratt said. Commercial farms often specialize in one crop. The monoculture model streamlines resources but makes crops more susceptible to disease and parasitic invasives. These practices also led to the clear cutting of huge swaths of land, largely defrosting upstate New York by the mid-19th century and destroying Indigenous hunting grounds.

As the nation expanded westward and commercial farms grew, a strong agribusiness sector emerged to sustain them.

The McCormick reaper, which was first made in Brockport, is one industrial-era invention that invigorated Canal town economies, Pratt said.

“It gets shipped down the Canal to those growing farms in the Midwest and helps expand cities and towns throughout the Canal region with new industrial jobs that are supplanting old agricultural ones,” he said.

Syracuse thrived during the Canal and railroad era, but global economic shifts eventually pushed factories and agribusiness elsewhere.

Today, entrepreneurs like Leah de Rosa are once again fostering people’s relationship to food and agriculture along the Canal corridor. For de Rosa, the goal is to make Plum and Mule a “food hub,” which she describes as a central location for foodstuff aggregation and distribution.

“We want to create a food hub here, like the original was right on Erie Canal,” she said. “And so we wanted to keep that going, because there aren’t any food hubs here in Syracuse.”

Born in New York City and raised in Bermuda, de Rosa knew nothing about food systems when she moved upstate 11 years ago.

During the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown, she was swept into a produce delivery initiative out of Syracuse’s Eden, a downtown restaurant partly owned by her sister, Eve, and brother-in-law, Adam Anderson.

When the pandemic subsided and Eden reopened in 2021, de Rosa acquired what was then “Eden Fresh Network,” alongside business partner Mark Pawliw.

Eden Fresh Network became Plum and Mule, a name that is closely knit to the history of the adjacent Canal.

“Part of our mission is to reduce the global footprint of people,” she said. “Instead of you having 10 different vendors bringing stuff to you, you have the one vendor that brings it to you, which is also why we like to work with the closer farms to us.”

De Rosa’s model is amplifying Community Supported Agriculture, a popular business throughout the Syracuse region. CSAs are most often run by farms and directly supply subscription-paying customers with a box of in-season produce.

“We usually work with seven to eight different farms, so you get a wider variety of items in your CSA box,” de Rosa said. “It really was interesting to see how people really resonated and wanted to connect to the source of their food.”

But farm-to-table is still an expensive lifestyle that many in Central New York cannot afford.

As the U.S. city with the highest child poverty rate, almost 50% of Syracuse children suffer from food insecurity, a metric closely linked to Onondaga County’s high residential segregation levels.

“Canal cities have all experienced a lot of redlining, and general discrimination has occurred within them — a kind of systemic divestment from, especially, communities of color,” said the Erie Canal Museum’s Derrick Pratt. “With the construction of the interstate highways in the 1950s, you have a lot of white flight. Oftentimes, grocery stores go with them, or seemingly grocery stores don’t find it profitable.”

De Rosa is in the process of getting SNAP benefits — federally funded, monthly food purchasing benefits provided to low-income households — approved for use at Plum and Mule.

While Plum and Mule nets the capital to support a more accessible business, de Rosa continues to host farmers markets on the South Side and free workshops at Brady Farm, one of Plum and Mule’s partners.

“I think it’s such a nice way, so people that may not have food, at least for that month, when their SNAP benefits are running out, are able to get some free food that might cook a couple of dinners,” de Rosa said.

Citing his hometown of Chittenango, located nearly 30 minutes outside Syracuse, Pratt said rural Syracuse faces many of the same issues, albeit for different reasons.

“We have one grocery store,” he said, “and everyone’s always worried, you know, every couple of years, there’s always a big fear that the lease on Tops isn’t going to be renewed or something. And then you have to drive 10, 15 miles to get your groceries, possibly.”

Bellows, SU’s food studies expert, added that “access to farmland is dwindling,” as larger and larger corporations buy more and more land.

But with CSA models and businesses like Plum and Mule, smaller farms are once again finding their place along the Canal corridor.

“When I first saw the wall back there where the Erie Canal used to come rolling down, I got emotional about it, really, just about that attachment to history,” de Rosa said. “Knowing we’re in a ‘food apartheid’ and trying to combat that is No. 1. The history of this building itself and the history of the Canal really touches me a lot.”