One sound seemed to follow Steve Kinne for more than 2,000 miles as he hiked the Appalachian Trail.

“Chick-burr”

The Air Force veteran was puzzled. Kinne kept glancing up at the trees, hoping the source would identify itself.

“Chick-burr”

“It drove me crazy that I didn’t know what it was,” Kinne said. “And I didn’t have time to really stop and go look for it.”

The call didn’t leave Kinne during his hike. Nor did it leave his mind as he continued north on the trail throughout the summer of 2006.

Once he returned home to Canastota, Kinne researched the bird calls he had heard, first tracking down what bird produced the “chick-burr.”

“Of all the birds, it happened to be a scarlet tanager,” Kinne said. “Now, here’s a brilliant red scarlet colored bird, you know, with black wings. But just, you know, something you think would be easy to see, but they’re up in the treetops. You can’t really see them too well when the leaves are out.”

That moment on the trail helped launch Kinne into birding. Not only did he become active in the Onondaga chapter of the Audubon Society (OAS), the 69-year-old led the club’s efforts in teaching dozens of others “birding by ear” — using the 36-mile Old Erie Canal Historic Park as his classroom.

Turning passion into education

Kinne has been an outdoor enthusiast ever since his time as a Boy Scout. While April through June are reserved for birding during the spring migration, he’s active outdoors year-round.

“I have my years kind of divided up into quarters,” Kinne said. “The spring quarter, that’s birds. Summers are trails, falls are hunting, winters are hemlock woolly adelgid surveys.”

Inspired by his experience along the Appalachian Trail, he grew particularly fond of identifying birds by their songs and calls.

But when he started going on trips with the OAS, Kinne found he was missing out on what birds the group was listening to. Though the group leader was picking out the birds and their songs, the bird’s actual name got lost by the time it reached the back of the line, like a game of telephone.

“I started working with a couple of people that were (in the back),” Kinne said. “I started asking them a question. ‘Well, what are you hearing? What does it sound like to you?’”

It didn’t take long before Kinne’s persistent curiosity caught on with others.

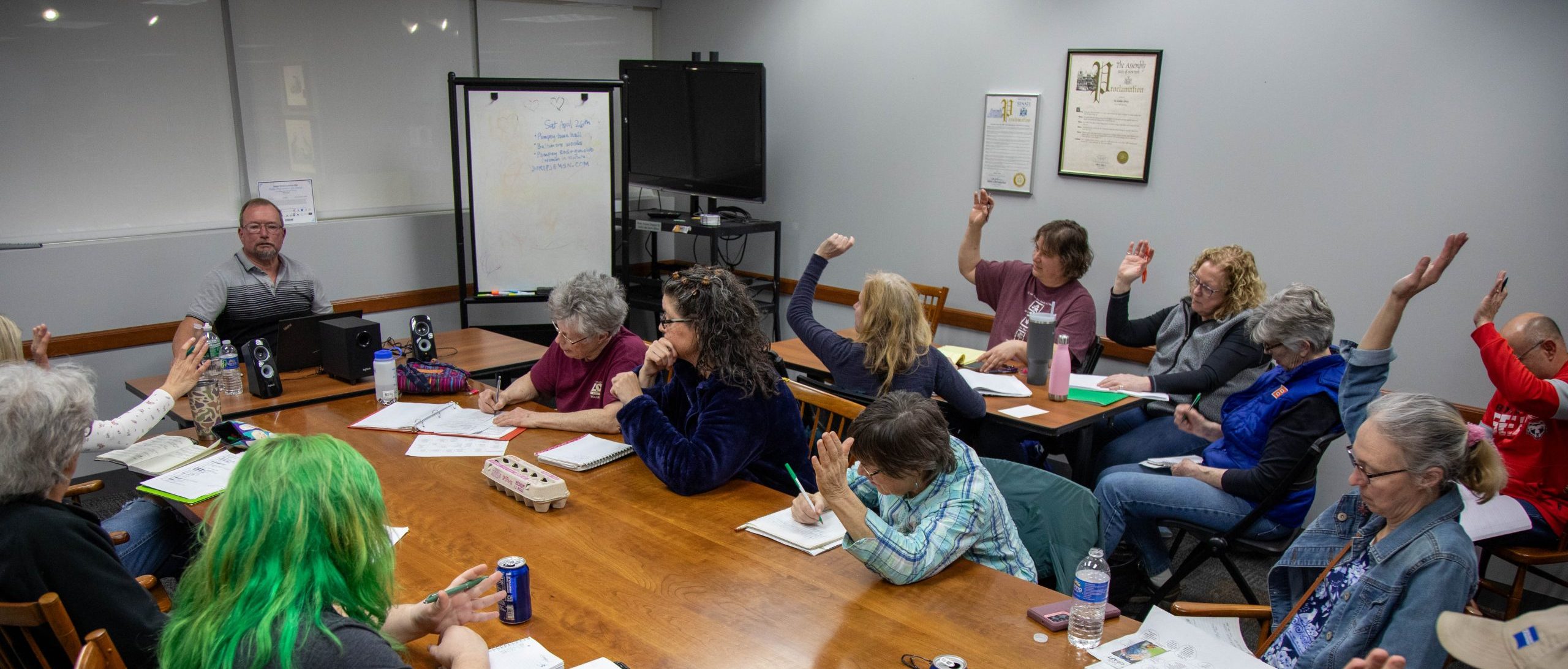

“We’d identify it, and when we did that enough, they finally said, ‘You know what, you got to teach a course,’” Kinne said.

Kinne started teaching the OAS’s beginning and advanced “Birding by Ear” courses in 2017. The courses started at a time when birding shifted from its senior-citizen-on-the-bench image to people of all ages and abilities actively identifying birds with their eyes, their ears and even their phones.

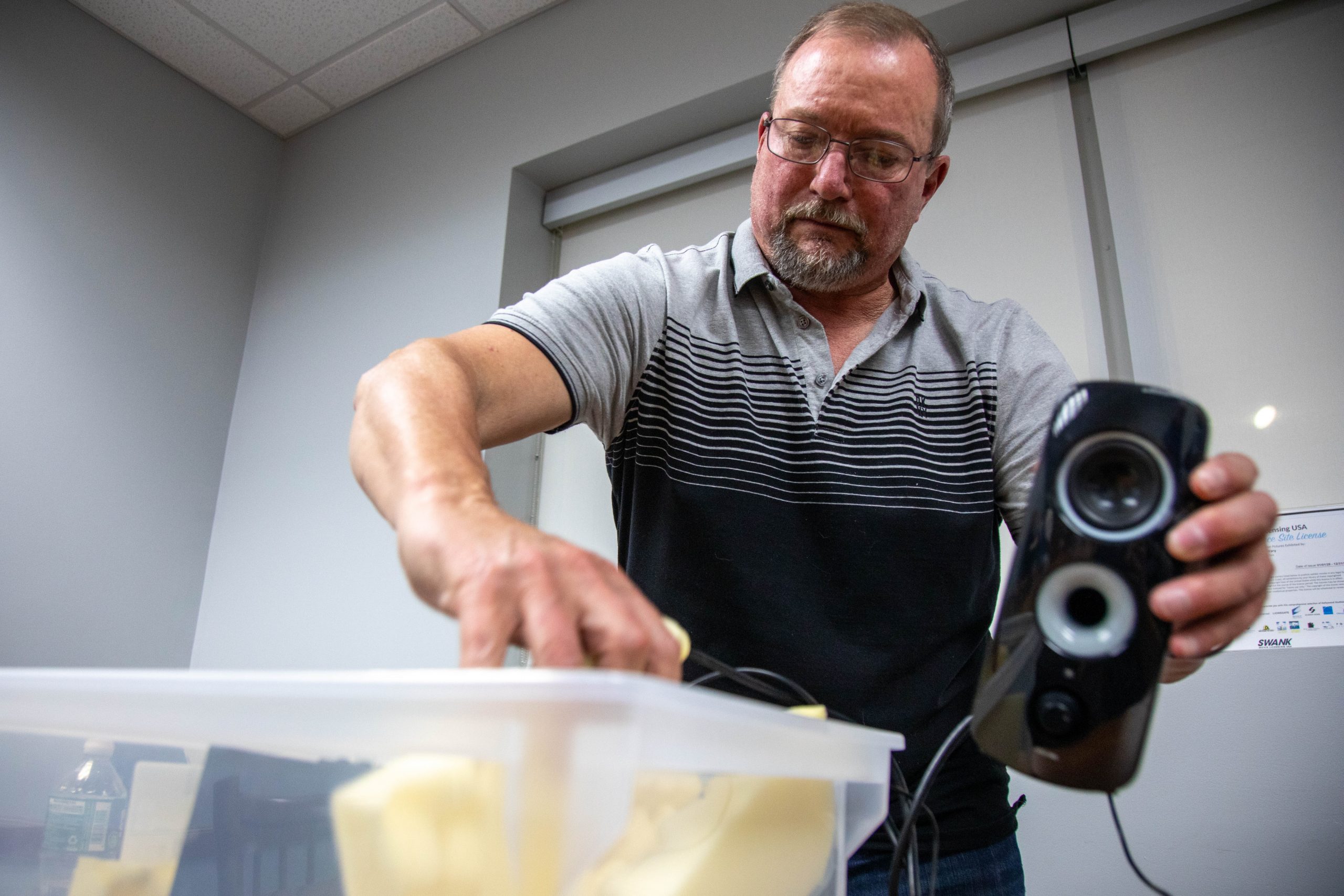

Kinne uses field trips to reinforce what he teaches during classes by giving his students a variety of ways to learn bird calls: mnemonics (an easy one for most is the chickadee as it sounds like chickadee-dee-dee), practice listening to recordings and listening-and-searching in the field.

Kinne uses these field trips to put students’ skills to the test. He brings the class out to a stretch along the Erie Canal between his town and Chittenango during the spring migration months.

Kinne wants to make sure he knows which birds will likely be in the area. With easy parking access, flat trails and a location away from residential areas, he can keep his eyes and ears open, ready to spot his next bird.

“The important thing about being a guide or the teacher is you’ve got to know what’s there,” Kinne said. “So the more time I spend on a couple of these areas, then the more familiar I am with what birds are typically there.”

With countless hours and trips spent walking the Canal, Kinne can regularly identify more than 90 bird species just along the waterway’s trails.

“The list would be long,” he said.“I would say you kind of have to sort of divide it up into what kind of habitat are you looking at.”

The variety of habitats along the Canal opens the opportunity for a wide range of birds to call the corridor home.

Matching habitat to bird, Kinne lists off an array of species in seconds: catbirds and yellow warblers in the trees and shrubs, spotted sandpipers along the water, field sparrows in the fields and red-winged blackbirds in the swamps.

Despite his ability to recall just about every bird in the county, Kinne doesn’t keep what birders call a “life list” that would contain the different species of birds a birder has recorded over their lifetime.

“I love being out in nature. I love listening to birds,” he said. “I would rather watch 10 birds for the rest of my life and really get to know their behaviors really well as opposed to doing 300 birds on my life list. That’s not my goal. Everyone’s got different goals for what they would like to do with birding.”

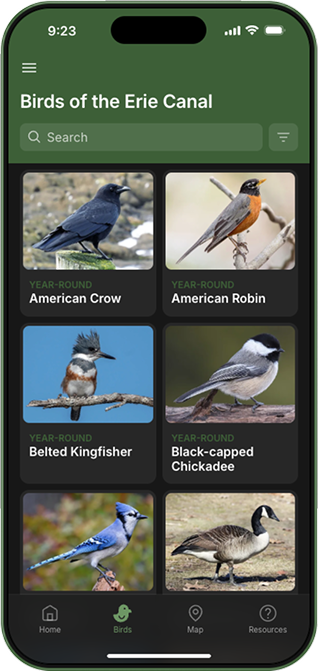

Kinne will also venture out if he is in search of a specific bird, like the eastern meadowlark in Fayetteville. Not wanting to waste a trip, Kinne uses Cornell’s eBird app to check out the latest reports of when and where birders are recording their bird sightings.

Phone apps making birding accessible

Mobile apps like Cornell’s eBird and Merlin have become useful tools for the birding community. No matter where people are, they have access to data on thousands of birds across the country.

“There’s a lot of people who really aren’t into birding, and then they get really excited because now they have this thing on their smartphone that they can actually hear what these birds are,” Kinne said.

Merlin can be especially useful for Kinne’s class. With a database of over 26,000 audio recordings, his students can practice their skills anywhere at any time. Additionally, through microphones on people’s smartphones, the app’s Sound ID can identify over 1,000 species of birds out in the wild.

Launched in 2014, Cornell’s app registered about 300,000 active users by 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic spawned a surge in birding interest, and the app surpassed 1.5 million by 2023.

While the app has extended the life lists for many birders and provides an introduction to bird songs, Kinne keeps his classes “old school,” as he describes it.